Everyone wants to know. Jesus answered by telling an astonishing parable.

The Bible tells us God is powerful and just, loving and wise, merciful, tender, patient, and persistent.

How do we know these things? Jesus himself, the Father’s Son, tells us. He tells us by direct teaching, by deed and action, and by example.

And, most memorably, through parables. To show us what the Father is like, Jesus told stories, deceptively simple tales of ordinary people – merchants and landowners, widows and fishermen, travelers and partygoers.

Among the most memorable of Jesus’ parables is the story we know as the parable of the Prodigal Son. However, this parable contains subtleties and depths that few of us grasp on first reading. For one thing, calling this the parable of the Prodigal Son is misleading, for it leaves out at least half the point of the parable.

A more accurate title would be the parable of the Two Lost Sons. Both sons are lost. Their father, who stands for God the Father, reaches out to both with an offer of forgiveness and reconciliation.

Properly understood, this parable vividly shows us God’s infinite love for men and women who are lost – both those who know they are lost, and those who don’t.

This story could also be called the parable of the Father’s Grace. The parable doesn’t simply focus on the two sons in their lostness; it focuses on the Father as he reached out to these sons and offered them relationship with himself – a relationship that they didn’t merit or deserve.

The first part of the parable tells the story of the younger son, a story of rebellion and the wreckage of a life.

“There was a man who had two sons, and the younger of them said to his father, ‘Father, give me the share of property that falls to me.’ And he divided his living between them. Not many days later, the younger son gathered all that he had, took his journey into a far country, and there he squandered his property in loose living”.

(Luke 15:11-13)

This was an act of rebellion, greater rebellion than we imagine as we read it with our Western eyes. In the context of the culture in which it was told, this offense was very grave. When the son said, “Give me the share of property that falls to me,” it was tantamount to saying, “Father, I wish you were dead and the property were already in my hands. Give it to me now.” It was a grave insult. Further more, the father having given it to him, the young man squandered it.

Another translation, Good News for Modem Man, captures the meaning of this: “He sold his part of the property. “The son was given a portion of land as part of his inheritance. This land was meant to stay in the family, but he sold it to an outsider. That was another act of rebellion, a violation of the “relationship, an insult to the family.

According to the customs of the time, that property, although in a certain sense given to the son, still belonged to the father. So the son squandered property that his father still had a right to and that the son was in some ways obligated to use for the provision of his father in his old age. The rebellion was tremendously magnified in this act.

Then the prodigal heaped insult upon injury. Remember that he was a good Jewish boy, born into a noble Jewish family. Not only did he insult his father and his family, he insulted his people. “He took his journey into a far country”; in other words, he went away to a pagan land, in effect rejecting his national and spiritual heritage.

Then the consequences of his rash rebellion:

“And when he had spent everything, a great famine arose in that country, and he began to be in want. So he went and joined himself to one of the citizens of that country, who sent him into his field to feed swine. And he would gladly have fed on the pods that the swine ate; but no one gave him anything”.

(Luke 15:14-16)

We see the progress from rebellion to wreckage of human life. What the young son encountered was not the unlimited sensory delights of his fantasy world; after a short-lived binge he ran up against his true condition: poverty, abject hunger, and humiliation.

Just think of it. What was a nice Jewish boy from a noble Jewish family doing feeding swine? It was

humiliating. However, that’s not the end of the story; it’s the turning point. The prodigal went from rebellion to wreckage, and then to repentance and restoration.

“When he came to himself he said, ‘How many of my father’s hired servants have bread enough and to spare, but I perish here with hunger! I will arise and go to my father, and I will say to him, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you; I am no longer worthy to be called your son; treat me as one of your hired servants.’ And he arose and came to his father”.

(Luke 15:17-20)

True repentance.

The son’s repentance began with honesty. He came to his senses and looked squarely at his position. He realized that he had brought it all upon himself. And this honesty progressed to an inward resolution. He said to himself: “I’ll exchange my role as a hired servant for this cruel master to become a hired servant for my father.” This demonstrates something very significant. The son knew something about the mercy of his father.

If the prodigal hadn’t known that his father was merciful, the idea would never have occurred to him to go back. After what he had done to his father, all he deserved if he returned would be to have abuse heaped upon him. But he had an inkling that if he went back, his father would at least take him back as a servant. Maybe he wasn’t absolutely sure of it, but he thought it was probably true. So, clinging to that hope, he resolved to go back.

He knew that there was a solution. And he went from honesty to resolution to action. The good thoughts were translated into actions: “He arose and came to his father” (verse 20).

Then we have the amazing scene in which this son was restored to his sonship:

“But while he was yet at a distance, his father saw him and had compassion, and ran and embraced him and kissed him. And the son said to him, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you; I am no longer worthy to be called your son.’ But the father said to his servants, ‘Bring quickly the best robe and put it on him; and put a ring on his hand and shoes on his feet; and bring the fatted calf and kill it, and let us eat and make merry; for this my son was dead, and is alive again; he was lost and is found.’ And they began to make merry”.

(Luke 15:20-24)

In order to fully appreciate this, we need to look again at the cultural background of the times. First of all, realize that the family home was not out in the country. In the Middle East, all the land that is farmed surrounds the village, while all the farmers’ houses are clustered together in a village. So this nobleman was likely to have had a large house within the village.

Second, life in the Middle East is lived mainly outdoors on the bustling, crowded streets. As soon as the younger son appeared on the horizon, everybody in the village would have known about it. He would have been exposed to the mockery and jeering of the whole village as he approached, because his rebellion was an act of rejection not simply of his father and his family but of the whole life of the village. Those who heard Jesus tell this parable would have understood it all in these terms.

Third, and crucial to the significance of the parable, is the fact that in the Middle East, a nobleman never runs. A nobleman is supposed to be known by his slow, dignified gait; for a nobleman to run in public would have been seen as a great disgrace and humiliation. So now imagine the homecoming. As the son approached the village, word came to the father, and what did he do? The father exposed himself to humiliation by running out to his son in order to quickly establish him and restore him and protect him from the mockery of the crowd.

And the son only got part way through his confession: ”Father, I am not worthy to be called your son.” He never got to the last line, “Treat me as one of your hired servants.” Why not? Before the son even got it out of his mouth, his father indicated that he would not allow him to be a hired servant. He ordered that the best robe, shoes, and a ring for his son’s finger be brought, symbolic gestures before the whole village that the son was restored to his sonship. Far beyond the expectation of this younger son was his father’s response to him!

The father called for a public celebration. A fatted calf would be a meal for about 100 people. It wasn’t a private affair. He said, “Let’s have a public feast and invite all of the leading people of the village. Let’s celebrate, because my son who was once dead is now alive. He who was lost is now found.”

The message of this first part of the parable is clear. God delights to restore full fellowship with himself to those who recognize their lost condition and seek his mercy. Jesus came for such as these and offered them the Father’s mercy.

Now we read the parable of the older son. His story is not an afterthought to the prodigal’s; it is essential and integral to Jesus’ full message.

First the setting: “Now his elder son was in the field” (Luke 15:25). What was he doing in the field? It’s clear that he was serving and laboring there. The word “field” was used once before, earlier in the parable, to refer to the younger son laboring in the fields of a pagan where he served the swine.

The older son served in the fields of his father, an obvious contrast. One son served his father, a good father. The other served a cruel, pagan master. But there’s a similarity here, as we’ll see later.

“As he came and drew near to the house, he heard music and dancing. And he called one of the servants and asked what this meant” (Luke 15:25-26). An interesting response. Why didn’t the older son just go in for himself and find out? Perhaps he was a little suspicious and didn’t fully trust his father. The older son didn’t seem confident that things would go well for him. He wondered, “There’s some revelry going on up there. What’s it all about?”

The servant told him, ”Your brother has come, and your father has killed the fatted calf, because he has received him safe and sound” (Luke 15:27). The servant is the bearer of good news: “Your brother has come back!” And he emphasized the relationship: “It’s your brother. He expected a great response of joy – hurrah! The prodigal has returned, and he’s restored! But the older brother was angry and refused to go into the house.

Again, understanding the culture will add to our understanding of the significance of the older brother’s behavior. The oldest son has a very special, defined role at a banquet feast in the Middle East. He’s expected to act as the co-host of the banquet, attired in a fine robe, greeting the guests as they come and go, telling the servants what to do, generally adding to the festivities by the importance of his presence. He’s expected to perform a public role along with the father.

Now imagine again the scene. People were bustling all around, and the fatted calf was being prepared. There was singing and dancing. And the older son refused to come in!

This wasn’t a private action – word of his refusal would have quickly reached the guests. Probably there was immediate silence as soon as everyone realized that the older son wouldn’t come in and take his place. In ancient times, a son could be executed for such misbehavior.

But what did the father do? “His father came out and entreated him ” (Luke 15:28). The father left the banquet to go outside and plead with his older son. This, too, was a public act. The father humbled himself before the people of his village and extended his mercy to his older son, just as he had extended his mercy to his younger son.

The older son replied, “Lo, these many years I have served you, and I never disobeyed your command; yet you never gave me a kid, that I might make merry with my friends” (Luke 15:29). What was missing as the son began to speak? He didn’t say “Father.”

When a son addresses his father, he begins by saying “Father.” The younger son always did it when he spoke to his father, even when he was in his rebellion. But this older son was so angry that he wouldn’t even acknowledge his father as father. “Lo, these many years I have served you.” This was the reply of a servant. Remember him toiling in the field.

The fundamental way the older son looked at his relationship with his father was then revealed. It’s as if he said, ”Unlike this good-for-nothing son, I’ve been a better worker. I’ve been an able servant. I’ve been a more productive employee, and I’ve never disobeyed your commands until now!”

What had been going on all along in the way the older son related to his father began to come out. He had the mentality of an employee in his attitude toward his father. He wanted suitable compensation for services rendered. And what did he ask for? “You never gave me a kid to make merry with my friends.” He didn’t want a public celebration or festivity with the family and village gathered together for a great time. He wanted something given to him so he could go off and gather a group of friends and have a private celebration.

Furthermore, he said to his father, “When this son of yours came” (Luke 15:30) – not “my brother,” but “this son of yours.” Just as he wouldn’t acknowledge his father, he wouldn’t acknowledge his brother. “When this son of yours came, who devoured your living with harlots, you killed for him the fatted calf.” He looked at this feast through perverse eyes. He saw it as if the father were giving payment to the younger son or rewarding him for the wonderful thing he had just done. “Oh younger son, you’ve taken half the share of our property and squandered the inheritance. How wonderful! I want to throw a feast in your honor.” The older son didn’t understand that the father wasn’t rewarding his younger son, but publicly expressing his joy that his son was alive and restored to him.

The older son did not express the proper respect and relationship with his father, but his father didn’t respond in kind. Instead he said, “Son.” He extended to him the term of respect and honor and endearment. “Son, you are always with me, and all that is mine is yours” (Luke 15:31).

It’s as if the father gently explained to him: “You totally misunderstand our relationship. You’re treating me as an employer. You’re treating your brother as if he’s a fellow hired servant who did something to get himself fired and shouldn’t be rehired. You’re treating me as your boss and looking compensation for services rendered. You’ve been living in this house with me all these years, and yet you don’t understand me at all. Don’t you see? You are always with me, and all that I have is yours.

“You don’t just need a kid from me as a gift to celebrate independently with your friends like a hired servant who has his own life to live. No, that’s not the way it is – you are always with me! We’re together! Everything I have is yours, and when I celebrate, it’s your celebration, and when you celebrate, it’s my celebration. We’re one. How can you talk like this?”

And the father went on, “It was fitting to make merry and be glad, for this your brother was dead, and is alive; he was lost, and is found” (Luke 15:32). The father said, “This is my younger son.” He didn’t treat him the way the older brother did. The father made it clear: “This is your brother. He’s not just my son. It’s your brother. You ought to be rejoicing with me.”

Now notice something very unusual about this parable. When studying things like this, we need to ask questions about what’s not there as much as we need to ask questions about what is there in the text.

There is no ending to this parable. Jesus has brought us to the point of ultimate suspense in the telling of the story. The father has pleaded with his older son to come in. We want to ask, on the edge of our chair, “What’s he going to do?”

Jesus didn’t tell us. Why not? Why does the parable conclude this way?

The parable ends this way because, as Jesus told it, it was not yet clear how the older brother would respond.

Jesus addressed this parable to the Pharisees and scribes who murmured against him, criticizing him that he received sinners and ate with them (see Luke 15:2). He concluded the parable with a direct challenge to those religious leaders. It was not simply a challenge to approve of Jesus. Jesus didn’t say, “What I’m doing is right, and you ought to approve of me.” But through the parable he said, “You need to understand that you yourselves are in the same position as the two lost sons. You need hear my words, and you need to receive my message. You need the forgiveness and reconciliation of God, even as these sons do.”

Those who heard the parable had a choice to make: Were they going to receive the father’s entreaty and invitation to come in, or were they going to stay outside, angry and unwilling to join in? The response was theirs, the response of those children who realized their own lostness and of those children who didn’t perceive it, because they lived as servants in the father’s house and didn’t know they were lost sons.

The outcome of the parable is still uncertain, because it depends in every case upon the response of

those who hear it. How will we respond? That will determine how the parable ends.

In this parable of the two lost sons, we see the mercy of God extended to us through his Son, Jesus. God is in the business of finding what was lost, and he humbles himself to reach out both to those who know and to those who don’t know they are lost.

God also wants us to understand something about his relationship with us through the parable. We are not hired servants. We are his sons and daughters. He enters into a relationship with us as a father. He doesn’t want us to desire a reward from him that we would in some sense share and enjoy independently of him. Our reward is to be his children and to be in his presence, sharing in his life and work, knowing that everything that is his is ours.

Finally, we see the reality that our relationship with God is reflected in our relationships with one another. This is not a parable primarily about the relationship between the two brothers; it’s a parable about the relationship between the two sons and their father. But the way the older son relates to his father is expressed in the context of his relationship with his younger brother. So it is with us: Often the way we relate to God is expressed in the way we relate to one another and in the mercy we extend to one another. It is expressed in the way we acknowledge the relationship we have with one another and also in the way we relate to those whom the Lord is calling to himself.Let’s answer the call of Jesus in this parable. Let’s come into our Father’s house and accept our place at the banquet. Let’s rejoice that we who were lost are found, and let’s rejoice in the finding of all those others the Lord would bring to himself.

This article, copyright © 1989 by Mark Kinzer, was first published in New Covenant, September, 1989, Volume 19, Number 2, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. Used with permission.

Image credits:

Top photo image of father hiking with his two sons in Lofer, Alps, © iStock photo ID:1190156310

Illustration of prodigal son famished and humiliated among swine: from google search – credit and illustrator unknown

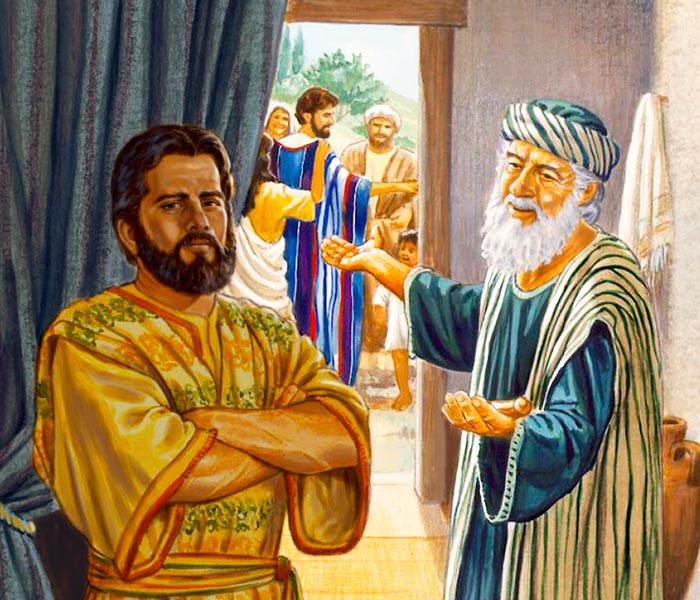

Illustration of the Father and the return of the Prodigal Son. This painting was formerly attributed to Francesco Fracanzo, c.1630–1650. Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, UK.Illustration of the father pleading with the older brother of the prodigal son: source

Dr. Mark Kinzer is Senior Scholar and President Emeritus of Messianic Jewish Theological Institute, a graduate school preparing leaders for service in the Messianic Jewish movement. Dr. Kinzer lives with his wife, Roslyn, in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where he also serves as Rabbi Emeritus of Congregation Zera Avraham, a Messianic Jewish synagogue which he founded in 1993.

He has been involved in ecumenical work since the 1970s, and has been a member of the Messianic Jewish – Roman Catholic Dialogue Group since its inception in 2000. He had an active teaching and leadership role for some 20 years (1970’s – 80’s) with The Word of God and the Servants of the Word in Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA and also with the wider network of international communities, called Sword of the Spirit. At its peak growth of 1400 people in the 1980s, The Word of God community comprised a diverse membership of Christians from many different traditions and denominations, including Catholics, Protestants, Orthodox, Pentecostals, and Messianic Jews.

Dr. Kinzer has written a number of articles and books, including Living With a Clear Conscience: A Christian Strategy for Overcoming Guilt and Self-Condemnation (1982), and Searching Her Own Mystery: Nostra Aetate, the Jewish People, and the Identity of the Church (2015), with a forward by Christoph Cardinal Schonborn, and Jerusalem Crucified, Jerusalem Risen: The Resurrected Messiah, the Jewish People, and the Land of Promise (2018).

Absolutely BRILLIANT!!! I will keep this with me forever..