Historically, when Christians have reflected on the end of the world, the last day and the Last Judgment, they have done so in two very different, almost contradictory ways. One of them is represented in the medieval hymn Dies irae, which is quoted and commented on below: it is characterized by images of terror and dread in the face of the Last Judgment. The other could be indicated by a few words from Paul’s letter to Titus (2:13), which consider the last day as a “blessed hope”, that is, something that we look forward to with great joy and happiness, since it consists of “the appearing of the glory of our great God and Savior Jesus Christ.” It seems to me that these two ways of looking at the end times correspond to two very different attitudes towards the event of salvation, the relationship with God, and the whole life of the Christian and of the Church.

There is a tremendously eloquent graphic picture that portrays the whole content of the hymn Dies irae, and which we should keep in mind as we describe and analyze this hymn. I am referring to Michelangelo’s fresco The Last Judgment, which is in the apse of the Sistine Chapel. We see Jesus depicted as “The Fearsome Judge” who with a stern gesture separates the righteous from the wicked. We see the righteous in glory, and the wicked suffering unspeakable torments in hell. These are the images that we have to prepare in our heads in order to understand the Dies irae.

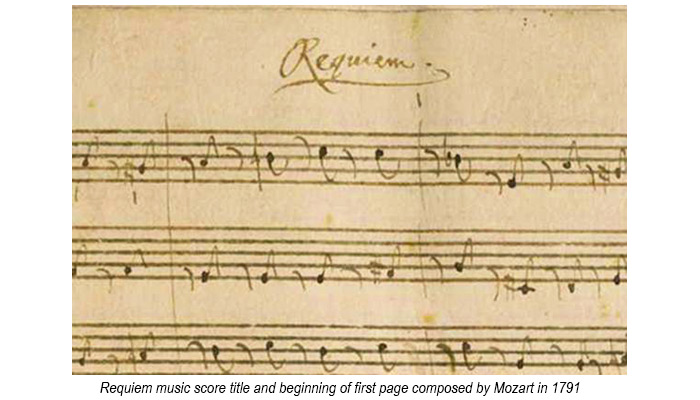

These graphic images can be accompanied by musical images, and the effect will be greatly enhanced. The Dies irae, as a medieval hymn, has its own notes of Gregorian chant; but also, because it is part of the ancient Mass for the Dead, it is included in all those more modern musical compositions that bear the name of “Requiem” (which is the first word of the introit of the Mass for the Dead). Moreover, it must be said that in all versions of the “Requiem”, the long text of the Dies irae takes up most of what is sung. Among these musical works, Mozart’s Requiem intones the Dies irae with particular intensity, conveying the spirit of something that is tremendous.

The hymn Dies irae was composed around the twelfth century. It was long attributed to the Franciscan Thomas of Celano (1200–1260), who was one of the biographers of St. Francis; but now it is “known” that it predates him… What is not known is who composed it or exactly when. Its character is of a sequence. Sequences are hymns in verse, rhymed, which are sung before the Gospel on certain special occasions. For example, the Easter and Pentecost sequences are very famous, and are still used in today’s Catholic liturgy, although they are often only recited rather than sung. Well, the Dies irae was used as a sequence for the Mass for the Dead in the Latin rite before the Second Vatican Council, a Mass that, as we noted before, was known as the “Requiem” because this was the first word of its “introit” (what today we would call the entrance antiphon), which begins by saying: Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine (“Eternal rest give unto them, O Lord”). The liturgical reform enacted after the Second Vatican Council abolished this sequence; it is most likely that this suppression was due precisely to the “change of spiritual attitude” towards the future coming of the Lord, a change to which I shall refer later.

Without a doubt, the Dies irae is a product of its time, and of a spiritual attitude that went back several centuries in the Middle Ages. It’s not that its author somehow “invented” that attitude; rather, he reflected it in his composition. But note that I have previously mentioned two other artistic compositions from later and very different periods: Michelangelo’s Last Judgment, completed in 1541; and Mozart’s Requiem, unfinished, but composed in 1791. Whereas Mozart’s work is the orchestrated Dies irae, Michelangelo’s is the Dies irae in graphic images. This shows us that the “spiritual attitude” of the hymn in question was strongly imprinted on the mental, liturgical and artistic posture of the West for the centuries that followed and, it should be said, up until the time of the Second Vatican Council itself.

Dies irae text

As it is not necessary to transcribe here the entire Latin text of the hymn mentioned, I limit myself to quoting in Latin its first stanza, followed by a fairly literal translation of the complete hymn (which I first made myself into Spanish, without attempting to fit it into the Spanish meter. The English translation followed later.) The hymn begins:

Dies irae, dies illa

solvet saec’lum in favilla:

teste David cum Sibylla.

[And the translation of that stanza and all the others (19 in total) is as follows:]

The day of wrath, O that day

when the world will be reduced to dust

as David and the Sibyl testify.What terror there will be then,

When the Judge comes

to examine everything rigorously!The trumpet, spreading its formidable sound

through the tombs of all countries,

will gather all before the throne.Death and nature will be stunned

When each creature is resurrected

to give an account to their Judge.A written book will be presented

which contains all things

for which the world shall be judged.When the Judge then takes his seat,

All that is hidden will then be revealed;

Nothing ill will go unpunished.What shall I say then, poor me?

Whose protection shall I call upon,

When even the righteous will be restless?O King of tremendous majesty

who freely saves those who are to be saved,

Save me, O fountain of mercy!Remember, O gracious Jesus,

that I am the cause of your coming to earth:

Don’t let me be lost on that day.Seeking me, you sat down tired;

To redeem me, you suffered the Cross;

Such great toil of work be not in vain!O righteous Judge who punishes,

Give me grace for your forgiveness

before the day of reckoning.I moan like a guilty man,

my face flushes with guilt;

have mercy, O God, on him who pleads with you.You who absolved the Magdalene

And who listened to the thief,

You also have given me hope.My prayers are not worthy,

but you who are good, treat me well;

Don’t let me burn in the eternal fire.Grant me a place among the sheep

and separate me from the goats,

By placing me on your right side.When You’ve defeated the damned

and have given them over to the cruel flames,

Call me with the blessed.I implore you, suppliant and prostrate,

with heart contrite as ashes;

Take care for me at my last hour.O day full of tears

When the guilty man will arise from the dust

To be judged!Have mercy on him, O God:

O merciful Lord Jesus,

Grant them rest. Amen.

Some biblical reminiscences

Certainly the hymn in question is replete with biblical reminiscences, especially from the Old Testament. The very expression “day of wrath” is found in Zephaniah 1:15, in a passage that announces precisely the “day of the Lord” as the day on which God will execute His judgment against His enemies. That passage from Zephaniah, as well as several lines in the book of Joel, and various passages in other of the Prophets, in fact, foretell the coming of a day when terrible things will happen, which are to be feared because they are the judgment of God. In the New Testament, both the book of Revelation and Jesus’ eschatological discourses in the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew 24, Mark 13, Luke 21) speak of cataclysms and disasters as an expression of that final judgment. Passages such as 2 Peter 3:10 also describe this universal dissolution.

What is often overlooked, however, is that those who should fear such judgment are the enemies of God and his people, not his faithful. It is a trial, not so much in the sense of a “judicial process to determine who is guilty and who is innocent”, but in the sense of a judgment or sentence that is enforced because a sentence had already been issued. That is why the friends of God, the Christians, the holy people, look forward to this day with longing and joy, because it will be the day when justice will finally be done to them and they will attain, through the resurrection, the fullness of the redemption they were expecting. We see it like this near the end of Jesus’ eschatological discourse in Luke 21:

There will be signs in sun and moon and stars, and upon the earth distress of nations in perplexity at the roaring of the sea and the waves, men fainting with fear and with foreboding of what is coming on the world; for the powers of the heavens will be shaken. And then they will see the Son of man coming in a cloud with power and great glory. Now when these things begin to take place, look up and raise your heads, because your redemption is drawing near.

Luke 21:25–28

Men who do not know God will be distressed by such portents and will be greatly afraid. On the other hand, the followers of Jesus – the Son of Man – seeing that “these things begin to take place,” will be encouraged and rejoiced because they are confident that Jesus, when he comes again “with great power and glory,” will come precisely to bring their redemptive work to completion and to establish completely and definitively the eternal Kingdom of God of which they will be a part.

That is why throughout the New Testament the second coming of Christ is presented to Christians as a joyful event, as the final victory of God and His people over all forces of evil. Revelation, if read with freshness and faith, is a book of hope and joy, which celebrates with triumphant songs that great victory of God and his people to culminate in the establishment of the New Jerusalem, in the new heavens and the new earth. In the epistles of Paul and the other authors we also find that longing and joyful hope for the final coming of Christ. He is certainly the Judge of all, but for his people he exercises this function of Judge not by putting them on trial but rather by doing them justice in the face of their persecutors and their enemies: he then manifests himself as their Redeemer and Liberator, who opens for them the doors of the definitive fulfillment of all God’s promises. This prospect of joy at the final coming of Christ is excellently captured in a text from the Letter to Titus, which was mentioned at the beginning of this essay:

For the grace of God has appeared for the salvation of all men, training us to renounce irreligion and worldly passions, and to live sober, upright, and godly lives in this world, awaiting our blessed hope, the appearing of the glory of our great God and Savior Jesus Christ.

Titus 2:11–13

The final coming of Christ is then his “glorious manifestation,” and since he is “our great God and Savior,” that coming is for us a “blessed hope,” something we look forward to with longing and joy.

Our “blessed hope” in Christ coming again in glory

That prospect of joy at Christ’s second coming and final judgment seems to have prevailed among Christians not only in apostolic times, but throughout the first three or four centuries of Christianity. It is true that the Pastors of the Church often warned the faithful about the coming judgment, but they did so first and foremost as an encouragement to a life of holiness and to turn away from every form of sin; not as a mere prediction of frightful calamities as if they awaited Christians. Such warnings, therefore, were accompanied by the certainty that the future coming of Christ was a cause of great joy for all Christians.

It would be a matter of lengthy reasoning to explore how and why that attitude of Christians changed to become more and more a sense of fear. In any case, it would not be surprising if, as the entry of new members into the Church became more massive from the fourth century onwards, when the Christian faith was accepted in the Empire and ceased to be actively persecuted, a certain relaxation also settled in the fervor of many, either because their conversion was not very deep or simply because it became easier to accommodate themselves to the way of life of the rest of society. In fact, this relaxation was undoubtedly one of the main motivations for the emergence of the ascetic or monastic movement in that same century, as a call to renew the authentic Christian life through a strong evangelical commitment.

In this environment of relaxation and lukewarmness, for many Christians, the continual warning against sin and the mention of the coming judgment against sinners became more necessary. Already at the beginning of the fifth century we find in St. Augustine the following reflection:

What kind of love for Christ is that of one who fears His coming? Aren’t we ashamed, brethren? We love him, and yet we fear his coming. Do we really love him? Could it not be rather that we love our sins? Let us hate sin, and let us love the one who is to come to punish sin.

Commentary on Psalm 96, sections 14–15

It is not surprising, then, that throughout the Middle Ages – the beginning of which we place shortly after St. Augustine – this spiritual attitude was accentuated, this emphasis on the “terrible” aspects of Christ’s coming and the Last Judgment, which instilled great fear in a majority of the Christian population. And, as we said at the beginning, this spiritual attitude of fear in the face of the Judgment took root and prevailed beyond the Middle Ages until reaching the present day. Indeed, today, outside the Christian realm, almost anyone to whom one mentions concepts such as “end of the world,” “Last Judgment,” and “Apocalypse” will react with an uncomfortable manifestation of dread.

But parallel to this, since the middle of the 20th century, numerous expressions of a renewed, fresh and committed Christianity have also emerged, which, without denying or renouncing its historical trajectory of twenty centuries, recovers appreciation for life, spirituality and attitudes of early Christians and is, therefore, a Christianity more connected with Scripture, with the Fathers of the Church, with missionary zeal, with the freedom of the Holy Spirit, with life in community. And it is only natural that in this renewed Christianity the spirituality of “blessed hope” should then re-emerge as we contemplate the future coming of Christ.

In the current Catholic liturgy of the Roman Rite there is a beautiful prayer – a part of Preface III of the Advent season – in which this renewed spiritual attitude of hope is reflected:

You have wanted to hide from us the day and hour in which Christ, your Son, Lord and Judge of History, will appear on the clouds of the sky covered with power and glory. On that day, tremendous and glorious at the same time, the figure of this world will pass, and the new heavens and the new earth will be born.

There we are told of Christ, certainly, as Judge, and it is affirmed that that day will be “terrible”, but at the same time it is said that it will be “glorious” and that, as “the figure of this world” is left behind, “the new heavens and the new earth will be born.” We could say that this hopeful prayer is a kind of synthesis of the two spiritualities: it mentions the “terrible” aspect of the Judgment, but gives more emphasis to the expectation of “power and glory” at the coming of Christ and to the certainty of “the new heavens and the new earth.”

The times in which we live are more and more like, in many respects, the times in which the first Christians lived. That is why we, the Christians of today, are recovering, and must continue to recover, the spiritual attitudes of those ancient brothers and sisters of ours. One of the most important among these attitudes is to await the second coming of Christ as a “blessed hope,” which causes us to take courage and “lift up our heads” even when we see bleak realities around us.

This article © by Carlos Alonso Vargas is an English translation of the original Spanish version, ¿Día de ira o dichosa esperanza? See more essays by Carlos Alonso Vargas on his website blog at https://carlosalonsovargas.medium.com/

Photo image credits:

The Last Judgment fresco painting by Michelangelo (cropped), from the Sistine Chapel, Vatican City. Image source in the Public Domain at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Sistine_Chapel_-_Last_Judgment.

Photo of the first page of Mozart’s Requiem music scoure sheet (image cropped), composed in 1791, now in the Austrian National Library, Codex 17561a, folio 1 (recto). Image source in the Public Domain at Wikimedia.

Carlos Alonso Vargas is a long-time leader in The Sword of the Spirit, who has served mainly in teaching and community building. With studies in philology and linguistics, he works as a translator and editor. He and his wife Dora have three adult children and five grandchildren and live in San José, Costa Rica.