I. What the Gospel of John tells us

The first chapter of the Gospel according to John tells us this:

1In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. 2 He was with God in the beginning. 3 Through him all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made. 4 In him was life, and that life was the light of all mankind. 5 The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it. […]

9 The true light that enlightens every man was coming into the world. 10 He was in the world, and the world was made through him, yet the world knew him not. 11 He came to his own home, and his own people received him not. 12 But to all who received him, who believed in his name, he gave power to become children of God; 13 who were born, not of blood nor of the will of the flesh nor of the will of man, but of God. 14 And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, full of grace and truth; we have beheld his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father. […]

16 And from his fulness have we all received, grace upon grace. 17 For the law was given through Moses; grace and truth came through Jesus Christ. 18 No one has ever seen God; the only Son, who is in the bosom of the Father, he has made him known.

John 1:1–5, 9–14, 16–18

II. Who was that Word who became flesh

The key text of that passage – which is, incidentally, also one of the key texts of the entire New Testament and of all Scripture – is verse 14: “And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, full of grace and truth; we have beheld his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father.”

The passage speaks of the “Word” and in verse 17 identifies him with Jesus Christ of Nazareth. Therefore, the Word that “became flesh” is Jesus of Nazareth, but it is also said of him that “he existed in the beginning,” that “he was God,” and that “all things (that is, the entire universe, absolutely everything created) were made through him.” In short: the eternal Word, who from eternity was God, becomes man, and that man is Jesus.

The Greek term logos, sometimes understood in other contexts as “discourse,” “reason,” or “treatise,” means first and foremost, and simply, “word.” This Logos we are told about is, therefore, the eternal Son of the Father: it is God himself; it is the second Person of the Trinity. John calls him “Word” probably because he is the one who gives form, order, and intelligence to all creation. Indeed, we are told that creation was made through this Word, and this echoes Genesis 1:1–31, where for each element of creation it is said that “God said”: what God says, his Word, his Logos, is the power that creates the entire universe.

And that same Word is the Son who has been with the Father from all eternity, from before creation. As we say in the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, He is “born of the Father before all ages, God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God.” That same Creed says that He is “begotten, not made”; that is to say, He is not a creature of God, but the very Son of the Father from eternity, of His very divine nature.

The language used by Saint Paul in the letter to the Colossians is very similar:

16 For by him all things were created: things in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or authorities – all things were created through him and for him. 17 He is before all things, and in him all things hold together.

Colossians 1:16–17

What verse 17 of this passage from Colossians means is that the entire universe continues to exist thanks to Christ; without him, nothing would exist. And verse 16, after affirming what John said – that the entire universe was created through the Word – adds that, moreover, everything was created for him: that is, he is the ultimate goal of the universe; everything is directed toward him, and, as Ephesians 1:10 says, everything will be unified under his authority as Head. Well then, precisely he, through whom everything was created and toward whom everything is directed, he who is before everything and who makes everything possible, he is the very one who became flesh! The eternal Son of God, who is true God, has become true man!

How the Word became flesh is narrated by Luke in the first chapter of his Gospel, in the story of the Annunciation (Luke 1:26–35): the invisible God becomes man in the womb of Mary, a virgin betrothed to Joseph; that is, God intervenes in human history through people with a concrete existence, with a genealogy and an occupation, members of a specific people, the people of Israel whom God had prepared for centuries precisely for this. And he becomes flesh by the power of the Holy Spirit (Luke 1:35; Matthew 1:18, 20): he is not conceived in Mary “by the will of man” nor by human biological seed, but in a completely supernatural way: he takes on flesh in the Virgin’s womb, meaning that even biologically he is born as the Son of God and not of a human father.

That is why we can affirm that Jesus is completely like us except for sin, and that at the same time he is the Word through whom all things were made, the eternal Son who is the complete and definitive revelation of God himself (John 1:1–3, 18; Hebrews 1:1–4).

Jesus Christ is therefore true God and true man: such is the great mystery of the incarnation, which as humans we cannot fully understand (that is why it is a mystery), but whose contemplation leads us to worship God for his love for all humanity and for each one of us.

III. The Christian doctrine of the incarnation

Why this doctrine is central to our faith

The term “incarnation” is not found as such in the Bible, but the concept itself is entirely biblical because it expresses what Scripture quite clearly teaches us: that Jesus of Nazareth, the man, is the eternal Word of God who became flesh, as we saw in the key text of John 1:14. Other texts that affirm this truth with different expressions are Romans 8:3 and Philippians 2:6–7, as well as the three Letters of John (1, 2, 3 John) which repeatedly insist that Jesus Christ “has come in the flesh.”

In the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed we say “for us men and for our salvation he came down from heaven.” God the Son became man with a very clear purpose, and that purpose was to show us his love and save us from sin and death. It was precisely because the Word became flesh – became man – that he could, as a man, die on the cross and rise again, thus making our salvation possible and fulfilling the eternal plan of God the Father: to bring about a new humanity, redeemed from sin, in which all of God’s promises and blessings in creation could be fulfilled.

For all these reasons, the confession of this truth is absolutely central to Christianity. The First Letter to Timothy states this very clearly:

16 Great indeed, we confess, is the mystery of our religion: He was manifested in the flesh, vindicate in the Spirit, seen by angels, preached among the nations, believed on in the world, taken up in glory.

1 Timothy 3:16

To summarize and reiterate, we can say then that the concept of incarnation means that a divine Person who existed before all creation, the eternal Son of God, begotten of the Father before all ages, the Word, has revealed himself in human history by being born of Mary as Jesus of Nazareth, so that he is true God and true man: fully God and fully man.

How this doctrine developed historically

As we have seen, Scripture clearly teaches the doctrine of the Incarnation, which was therefore something already believed and upheld by the first generation of Christians, as transmitted by the apostles. The New Testament, as can be seen in the quotations transcribed above, testifies that the first Christians believed this. However, it took Christians several centuries, certainly not to come to see or believe that this doctrine was part of the Gospel, nor to discover it, but rather to formulate it in a way that was comprehensible to rational thought.

At the beginning of the fourth century, a serious controversy arose with a priest from Alexandria, Egypt, named Arius. He did not intend (as he said) to deny the Incarnation itself, but argued that even if the Word had been “begotten” by the Father, this must have occurred at some point in time, and that therefore “there was a time when the Word did not exist.” That is, he denied that the Son had existed from eternity just as the Father did; he denied that “in the beginning was the Word,” and in that sense, he made Jesus Christ inferior to the Father in nature; he made it so that he was not truly God and that, at least implicitly, he was created by Him. This theory, called Arianism, spread throughout much of the Church at the time, even after the Council of Nicaea in 325, where it was clearly condemned. The great hero who staunchly defended the true doctrine of the Incarnation was Saint Athanasius, also from Alexandria (296–373).

The Council of Nicaea, in the aforementioned year, convened specifically to resolve this issue, as the majority of bishops, following Athanasius – who was still a deacon at the time – were clear that Arius’s theory was incompatible with what the Church had always maintained. The Council finally achieved a clarity in the formulation of this doctrine that has been fundamental to Christianity and is expressed in the profession of faith known as the Nicene Creed (to which the Council of Constantinople, in 381, added an important clarification regarding the Holy Spirit, and other details, which is why the Creed is more accurately called the “Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed”). Of course, this clarity in formulation does not fully explain or unravel the mystery of the Incarnation (it remains a mystery!), but it does help us to understand it in faith, to worship God for the greatness of this mystery, and to become aware of its practical consequences for our lives.

The Nicene “Symbol” or Creed, in that first version of the year 325, says the following when referring to Christ:

We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ, the Son of God, the Only Begotten, begotten of the Father, that is, from the substance of the Father. God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made, of one substance with the Father, through him all things were made…

(In my 2019 article, “ The ‘True’ Nicene Creed,” I give more details about the Council of Nicaea and the differences between this first version of the Creed and its final form approved in Constantinople, which is the one we know.)

With its emphatic statement that Christ is “begotten, not made” and “of one substance with the Father,” the Council of Nicaea made it clear that the Father and the Son are coeternal and consubstantial. But the controversies continued for more than a century, and the question arose: how could the eternal Son, who is God coequal with the Father, share in our flesh in such a way as to become man like us?

The Councils of Constantinople in 381 and Ephesus in 431 addressed other facets of the question, and finally, in 451, the Council of Chalcedon defined the orthodox doctrine of the Incarnation: it declared that Jesus Christ is true God and true man, consubstantial with the Father in his divinity, but consubstantial with us in his humanity, in all things except sin. It declared that the Lord Jesus Christ has two natures united in his one person: a divine nature and a human nature. This is the text of the Council of Chalcedon:

“One and the same Christ, the only-begotten Son and Lord, must be acknowledged in two natures, without confusion, without change, without division, without separation, the difference of natures in no way being erased by the union, but rather each nature retaining its own property and concurring in one person and one hypostasis, not divided or partitioned into two persons, but one and the same only-begotten Son, God the Word, Lord Jesus Christ.”

This union of the divine and human natures in one person (technically called the “hypostatic union”) is a common confession of the Christian Church, whether Byzantine Orthodox, Catholic, or Protestant in its various expressions and branches. Christians of the so-called “Ancient Eastern Churches” or “Oriental Orthodox” (such as the Copts, Armenians, and Syriacs) do not accept the formal definition of Chalcedon, but in reality, they do believe the same as we do: that Christ is one person, both human and divine. Thus, this definition of the Council of Chalcedon, although not explicitly stated in Scripture, has proven so useful in defining the boundaries of the Christian faith regarding the person of Jesus Christ as the one Mediator.

How are we to understand the term “nature” (or “substance”) used in those ancient definitions? It refers to what truly is, the “true being,” as opposed to mere “appearance.” Regarding Jesus Christ, we could break down this concept as follows:

- That Jesus Christ is God himself: he is not “like God”; he is God.

- He is not God “in the appearance[CV1] of a man”, but rather he is man.

- He is not “only man” nor “only God”, but God made man.

- He did not cease to be God when he became man; he did not exchange divinity for humanity, but upon his pre-existing divinity he historically assumed humanity, so that from that moment on he is both human and divine: God-man.

- There was no moment when “he began to be God” (being God necessarily implies being so from the beginning, pre-existing all of creation), but there was a moment when “he began to be man” (when he became flesh), and from that moment and for all eternity he is God and man at the same time.

In short, Jesus Christ, the only Son of God, the Word of God made flesh, is one divine person with two natures: divine and human. [CV2] He is not two persons, but one person. And He is a divine person: otherwise, we would not worship Him, because Christians worship only God and never any creature. But these two natures are inseparable: we can never think of Christ as man without simultaneously thinking of Him as God, and vice versa.

Certain current theological trends that are problematic

Nineteenth-century German liberal Protestantism, heavily influenced by the rationalism of the Enlightenment, questioned many of the main doctrines historically developed and preserved by Christianity. From this emerged a theology that can be called “liberal” or “secularist” (that is, one that conforms to worldly trends rather than the truths of the Christian faith). This theological current, still strongly present today among influential Protestant and Catholic theologians, went so far as to question or even deny very important aspects of what we believe about Jesus Christ.

It is said, for example, that Jesus is simply a man “uniquely endowed with the consciousness of God,” or that he “knew God in a way that no one before him had known,” or that he “taught a very high morality without transgressing the limits of a purely human view of himself.” According to this view, Jesus was a first-century Jew like any other, but with a moral integrity and religious genius that make him unique in history. Many of those who think this way also assert that the entire “divine” dimension of Jesus Christ, which they call “exalted Christology” or “Christology of exaltation” (and which includes, of course, his virginal conception and bodily resurrection), are mythical ideas invented by Christians in the years and centuries following the “historical Jesus” (whom they artificially contrast with the “Christ of faith”).

It is evident that such positions depart radically from the doctrine of the Councils of Nicaea, Constantinople, Ephesus, and Chalcedon, and ultimately empty the term “incarnation” of its meaning. They depart from the basic truth that “the Word became flesh” and that “he was manifested in the flesh,” and therefore seriously undermine the very foundation of the Christian faith. For all these reasons, we, as authentic Christians, must be on guard against these theological tendencies, which manifest themselves in many ways – especially through ambiguities or confusing statements – and in our time primarily through certain widely distributed novels and films, programs and broadcasts on the internet, and so forth. We must keep firmly in mind the warning of the Second Letter of John:

7 Many deceivers have gone out into the world, those who do not confess that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh. Such a person is the deceiver and the antichrist. 8 Be on your guard so that you do not lose what you have worked for, but may receive a full reward. 9 Anyone who goes beyond Christ and does not abide in his teaching does not have God; whoever abides in his teaching has both the Father and the Son. 10 If anyone comes to you who does not bring this teaching, do not receive him into your house or even greet him. 11 Anyone who greets him shares in his wicked works.

2 John 7–11

- See Part 2: Results and Practical Consequences of the Incarnation

This essay, The Incarnation of the Son of God, Part 1, and Part 2, © by Carlos Alonso Vargas is an adapted English translation of the original Spanish version La Encarnación del Hijo de Dios. See more essays by Carlos Alonso Vargas (in Spanish) on his website blog at https://carlosalonsovargas.medium.com/

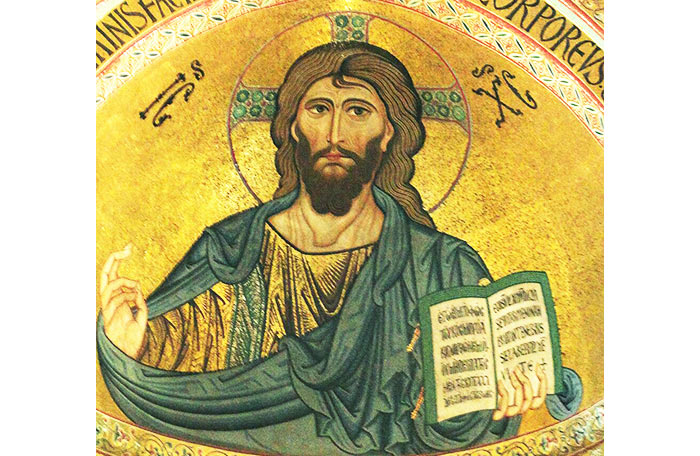

Top image credit: Mosaic of the Christ Pantokrator (cropped) in Duomo di Cefalu, Sicily, Italy. The cathedral dates from early 12th century. Source of image from Wikimedia Commons, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

Carlos Alonso Vargas is a long-time leader in The Sword of the Spirit, who has served mainly in teaching and community building. With studies in philology and linguistics, he works as a translator and editor. He and his wife Dora have three adult children and five grandchildren and live in San José, Costa Rica.