The following selection of quotes are from Igino Giordani (1894 – 1980), a Christian historian and lay leader in the Focolare Catholic / Ecumenical renewal movement, and a selection of quotes from early Christian writers from the second century A.D.

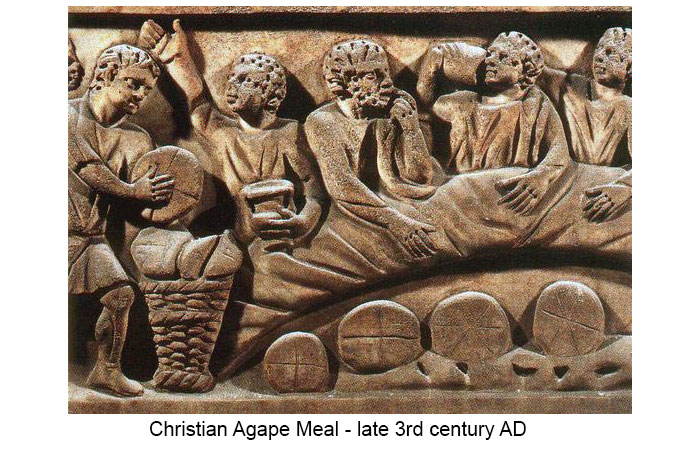

The Christians of the first centuries saw themselves as a distinct people in the world. They showed their peoplehood by caring for one another as brothers and sisters in the new covenant, by making a separation between their own way of life and that of the people around them.

The early Christian writers describe how the first Christians fulfilled their commitment to care for each other. Aristedes, aGreek Christian of the second century, gives us this picture:

“They love one another and do not overlook the widow and deliver the orphan from him who treats him harshly. He who has supplies the needs of him who has not, without grudging. If they see a stranger they bring him under their roof and rejoice over him as a real brother, because they call themselves brothers not according to the flesh but according to the spirit. And whenever one of their poor passes from the world, each one of them according to his ability gives heed to him and carefully sees to his burial. And if they hear that one of their number is imprisoned or afflicted on account of the name of their Messiah, all of them anxiously minister to his needs, and if possible redeem him and set him free. And if there is among them any that is poor and needy, and if they have no spare food, they fast two or three days to supply the needy with what they need”.

(Apology, 15:7)

At the end of the second century, the African Christian Tertullian adds these details:

“On the monthly day, if he likes, each puts in a small donation, but only if it be his pleasure, and only if he be able, for there is no compulsion, all is voluntary. These gifts are… taken … to support and bury poo people, to supply the wants of boys and girls destitute of means and parents, and of old persons confined now to the house; such too as have suffered shipwreck; and if there happen to be any in the mines or banished to the islands or shut up in the prisons for nothing but their fidelity to the cause of God’s church, they become the nurslings of their confession” .

(Apology, 39)

A modern historian, Igino Giordani, offers these descriptions: “Assistance was given to all who could be reached, but it was given first of all to companions in faith and in a spirit of brotherhood. Tertullian wrote:

‘Although the good which is done to strangers is greater, it does not come before that which is due to one’s neighbors.’ … Because the Christians loved one another as brothers and called one another by that name – so that it could be said that they ‘love one another almost before they know one another’ – this love, translated into works of charity, created a real and effective solidarity between the rich and the poor…

“The virtue of hospitality was practiced on a vast scale, since every Christian traveling for business, necessity, or relaxation immediately sought out the Christian community wherever he arrived; and in it he did not feel a stranger”.

(The Social Message of the Early Church Fathers, 1944, by Igino Giordani, pages 304, 310)

The Christians’ sense of being a distinct people, living their own holy way of life in the midst of nations, was a frequent theme of the early Christian teachers. At the end of the second century Clement of Alexandria boldly stated the contrast between the ways of life of Christians and other peoples in this way:

“Let the Athenian follow the laws of Solon, and the Argive those of Phoroneus, and the Spartan those of Lycurgus; but if you enroll yourself as one of God’s people, heaven is your country, God your lawgiver. And what are the laws? ‘You shall not kill; you shall not commit adultery; you shall not seduce boys; you shall not steal; you shall not bear false witness; you shalt love the Lord your God.’ And the complements of these are those laws of reason and words of sanctity which are inscribed on men’s hearts: ‘You shall love your neighbour as yourself; to him who strikes you on the cheek, present also the other; you shall not lust, for by lust alone you have committed adultery’ “.

(Exhortation to the Greeks,10)

The Christians of the first centuries recognized that if they were to obey the commandments they needed to follow different customs from those of people around them who did not acknowledge God or his law. Giordani describes some of the conclusions the early Christians drew regarding the kind of spiritual separation to be made between themselves and the surrounding society:

“The gospel teaching demanded that Christians stay away from all those places and exhibitions of one sort or another in which monotheism, or Christ as God, or his moral law might be offended.

“Therefore they stayed away from religious festivals, they did not go to the temples, adorn their houses with garlands on the festival days, light torches, or wear wreaths upon their heads, etc. They continued to frequent the baths, the basilicas, and the forums in the daily round of business, but they did so with a feeling of revulsion, and they kept away from those places too as much as possible because of the records of idolatry, the exhibitions of corruptions, and the fraudulent transactions they were bound to run into when they entered them. The baths, for example, had in a great number of cases become real brothels and the attendants acted, even legally, as procurers.”

(source: The Social Message of the Early Church Fathers, 1944, by Igino Giordani, page 54).

The Christians’ refusal to exchange their own way of life for that of the non-Christians they lived among was recognized as a key issue between Christianity and pagan society. Giordani tells of one instance in which “Seven men and five women of Scillium were condemned to death by the proconsul of Asia because they refused to ‘return to Roman customs.’ The sentence of death read: ‘Since Speratus, Nartallus, Ciuinus, Donata, Vestia, and Secunda have confessed that they live in the manner of the Christians and since, when a reprieve was offered them if they would begin again to live after the manner of the Romans, they have persevered in their obstinacy, we condemn them to be put to the sword.'”

This article was first published in Pastoral Renewal, July/August 1988 Issue, Volume 13, Servant Ministries/The Center for Pastoral Renewal, Ann Arbor, Michigan USA. Updated in 2020 for Living Bulwark.

Short bio: Igino Giordani (1894-1980) was an author, journalist, politician, ecumenist and expert in patristic studies. He remained one of the most representative figures of the 1900s, a highly gifted individual who left a profound mark and opened prophetic perspectives on a cultural, political, ecclesial and social level.

Born in 1894 in Tivoli, the first of 6 children of Orsolina and Mariano, a bricklayer, Giordani was given the opportunity to study, thanks to the help of a sponsor. In 1915 he entered the army to fight in the First World War. An official in the trenches, he admitted later that he never wanted to shoot at the enemy. Nevertheless, he earned the Silver Medal for Bravery. He also received wounds, the pains of which remained with him for the rest of his life. He went on to get his degree in letters, he began teaching in Rome, and he married Mya Salvati. Theirs is a story of great yet delicate love, from which were born 4 children: Mario, Sergio, Brando and Bonizza.

On June 2, 1946, he was elected to the government and became part of those “founding fathers” who laid down the ideal foundations of the Italian republic. He was re-elected in 1948, and in 1950 he became a member of the Council of Nations of Europe in Strasburg.

As a writer he published more than 100 works (an average of 2 every year), works translated into the main languages. He also authored countless reviews, commentaries, articles (over 4,000), letters and speeches.

An exemplary Christian

Out of a situation of suffering in the military hospital, Giordani at 22 years of age, sensed an initial call to holiness of life, a call reinforced by the writings of Catherine of Siena. He became a third order Dominican out of love for her, “the first who ignited the flame of the love of God in me.” As a Christian, he approached his work with an evangelical spirit, seeing in it his vocation. His most significant writings – ever contemporary – came forth from a deep knowledge of the history of Christianity and of the Fathers of the Church. Herein lies the solid spiritual and theological formation which characterized him. He put it to good use through his vigorous activity in fostering the Christian impact on culture, the spiritual formation of the laity and of priests and religious.

A forerunner in ecumenical dialogue

Giordani, already in the 1930s, marked out elements for the Second Vatican Council. He studied, he translated, he explained the Fathers of early Christianity, at a time when they were almost forgotten. Their works formed the basis of his “Christian Social Message,” one of his better known works. He entered into them in such a way that Italo Alighiero Chiusano defined him as “a sort of ancient Father of the Church to whom God gave the privilege of rising and acting in our midst today.”

Joined the Focolare Movement

In September 1948, when he met Chiara Lubich (founder of Focolare), this encounter marked for him the beginning of a new experience that was to envelop him completely; his spiritual membership was exceptional for his humility, transparency and unity. He would later say: “All of my studies, my ideals, the events of my life seemed directed towards this goal… Before, I had looked for it, now I had found it.”

Captivated by the evangelical radicality of the “spirituality of communion” that Lubich spoke of and lived out, Giordani saw in it the possible accomplishment of the dream of the Fathers of the Church: to open wide the doors of the monastery so that holiness of life would not be the privilege of just a few, but a mass movement among Christians. With all his mind and heart, he entered the Focolare Movement and came to be known as “Foco”, because of his burning love that bore witness and reached out to others. Furthermore, with his “yes”, he became a providential instrument by means of which the Focolare foundress would reach an ever deeper understanding of the charism she had received.)

(source of bio: https://www.focolare.org/en/news/2004/06/14/italiano-igino-giordani-unanima-di-fuoco/)

Interesante artículo. Gracias.