It takes only a few seconds to see a Rembrandt painting in a museum gallery. It takes a much longer time to comprehend why that painting is by common consent a great work of art.

This is the same difference as looking at a page of text and actually reading it. To read a text and understand it requires that we know the vocabulary it uses, and its syntax and grammar. And just as every verbal text is based on certain customs and conventions, so every visual creation is. Just as we cannot understand a text without entering into the author’s thought processes we cannot understand or appreciate a work of art without first learning its visual language and accepting the intentions of the artist who created it.

Some verbal texts are easy to understand. They have an obvious meaning, one that is familiar to us. But others challenge our understanding, and in many cases surpass it. We often discover the author is saying something we cannot understand, at least not at first. Perhaps we need to look up some words in a dictionary, or even educate ourselves in the subject being written about.

The same is true for Rembrandt’s visual creations. And for this reason it is hardly scientific to expect that Rembrandt will make sense to us if we insist on viewing his work from an intellectual and spiritual perspective he did not share – and indeed could not have imagined. This is not a problem unique to Rembrandt scholarship. It is a problem historians constantly struggle with. People living in cultures and civilizations distant from us in time and space have always done things that were rational for them, given their foundational assumptions, but which appear irrational to us.

As a group twentieth-century intellectuals have found it difficult to accept the extent to which religious and spiritual questions motivated persons who lived in the Seventeenth Century. It has even been more difficult for persons in our time to acknowledge the belief, almost universally held previously, that the realm of the spirit is as real as the physical realm.

For persons committed to the secular tradition it has become virtually axiomatic that scientific thought requires materialism, on the assumption that materialist beliefs are unambiguously supported by the findings of science. But this is a position virtually no one in the Seventeenth Century would have found comprehensible. It is certainly not one Rembrandt would have held.

If we wish to understand the events of that time – including its art, and certainly including Rembrandt’s art – we must enter into the beliefs which prevailed then, rather than imposing our more secular way of thinking on to that distant time.

The scientific revolution has taught us to believe that everything can be understood rationally. But the very clarity of this new way of thinking is now making it apparent that there are many things that cannot be understood solely by applying the tools of analytical logic, and art is one of them.

What is it that makes one artistic creation beautiful and another ordinary? Why are some works of art carefully preserved in museums, generation after generation, while others are discarded? Those are the kinds of questions we are now able to ask, but have proven incapable of answering. We now understand the physical qualities of Rembrandt’s paintings to a remarkable degree, but we still cannot explain in scientific terms why his works are considered masterpieces.

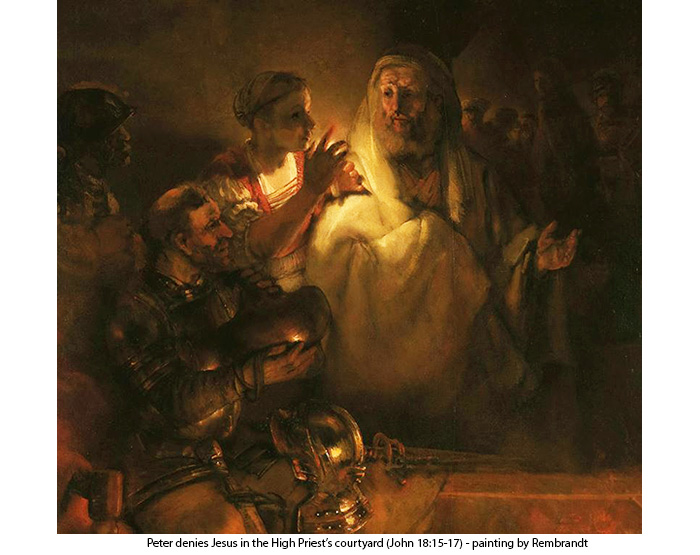

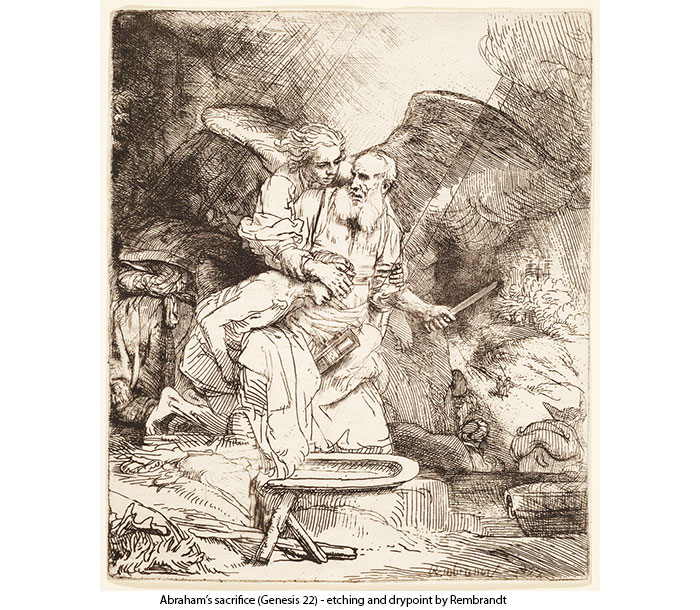

Rembrandt lived when the Modern Era’s secular culture was forming, and although it provided him with the freedom to paint and etch in a new way, he was not committed to its view of reality. As a result, he was able, in an apparently effortless way, to combine the most holy with the most mundane – transforming the ordinary into the spiritual, combining the transcendent and the historical. It is this, I am convinced, which distinguishes him, not only from other artists of his time, but also from us.

This brief article is excerpted from an essay, Seeing The Light: Rembrandt’s Religion – Introduction, © 2015 by Ivan J. Kauffman, published on Academia.edu.

Image credits for artwork by Rembrandt van Rijn: The Denial of Saint Peter (1660), Sacrifice of Abraham(1655), and Christ Preaching (1652). Images in the Public Domain.

Ivan J. Kauffman (1938-2015) grew up in one of the oldest surviving lay evangelical communities, the Amish Mennonites. Educated as both a Mennonite and a Catholic, he has been active in Mennonite Catholic dialogues from their beginnings in the 1980s, and was a founder of the North American grassroots Mennonite Catholic dialogue, Bridgefolk, which meets regularly at Saint John’s Abbey, Collegeville, Minnesota, USA. He identified as a Mennonite Catholic.