When most Christians think of prophecy, they have in mind the great prophets of the Old Testament: Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and the rest. In fact, most Christians probably think of prophecy only as an Old Testament phenomenon. Yet the pages of the New Testament are filled with the influence, the words, and even the names of the prophets who lived after the death of Jesus. The Acts of the Apostles alone records at least five instances of prophetic actions.

The first instance occurs in Acts, chapter eleven. A prophet named Agabus, speaking under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, predicted that a famine would soon come to the whole world. The writer of Acts mentions that this famine did in fact take place during the reign of the emperor Claudius. The prophetic revelation given through Agabus enabled the early Christians to prepare for the disaster in plenty of time.

Somewhat later we read of the decision made at Antioch to send out Barnabas and Paul as missionaries (Acts 13:1-4). As the leaders of the church, among whom were prophets, prayed together, the Holy Spirit spoke to confirm their decision to send out the two men.

The fifteenth chapter of Acts mentions two men, Judas and Silas, “who were themselves prophets.” They encouraged and strengthened the disciples at Antioch through an inspired discourse. And finally, in the twenty-first chapter, we read these accounts of prophets warning Paul of the dangers that would face him in Jerusalem:

We looked for the disciples and stayed with them for a week. Under the Spirit’s prompting, they tried to tell Paul that he should not go up to Jerusalem; but to no purpose.

Acts 21:4

This man had four unmarried daughters, gifted with prophecy. During our few days stay, a prophet named Agabus arrived from Judea. He came up to us and taking Paul’s belt, tied his own hands and feet with it. Then he said, “Thus says the Holy Spirit: This is how the Jews in Jerusalem will bind the owner of this belt and hand him over to the gentiles.”

Acts 21:9-11

The early Christians prophesied regularly when they met together (1 Corinthians 11:4-5; 14:3); converts prophesied at the laying on of hands (Acts 19:6); prophecy is listed frequently as one of the gifts Christ bestows upon the Christian community (Romans 12:6; Ephesians 4:11-12; 1 Corinthians 12:10,28, 29); prophets are a part of the foundation of the church (Ephesians 2:20)1; it was to the apostles and the prophets that the revelation of the full plan of salvation was given (Ephesians 3:4-6); prophets are mentioned in connection with the ministry of Timothy (1 Timothy 1:18, 4:14); Christians are encouraged to value prophecy (1 Thessalonians 5:20) and to seek it more earnestly than the other gifts (1 Corinthians 14:1). Christian prophets emerge from the pages of the New Testament as a major element in the early church.

The record of prophetic activity extends well beyond the New Testament. The Didache, a church manual from the early second century, makes several references to prophets. Its instruction on how to relate to prophets speaks clearly of the presence of prophetic activity. Later, about the year 162, the Christian apologist Justin mentions prophecy in a dialogue with a Jewish rabbi, the Dialogue with Trypho. He points to the gift as part of his evidence for the truth of Christianity: “From the fact that even to this day the gifts of prophecy exist among us Christians, you should realize that the gifts which had resided among your people have now been transferred to us.”2

Similarly, Irenaeus of Lyons speaks in the late second century of the presence of the gift of prophecy among Christians: “For this reason does the apostle declare, ‘We speak wisdom among the mature,’ terming those persons ‘mature’ who have received the Spirit of God and through the Spirit of God do speak in all languages, as he himself also spoke. In like manner we do also hear many brothers in the Church who possess prophetic gifts, and bring to light for the general benefit the hidden things of men…3

We even have a prophecy recorded from the late second century. Melito, bishop of Sardis and a renowned holy man, preached a famous sermon On the Pasch. At the end of the sermon he broke into prophecy:

Who will contend against me: Let him stand before me.

It is I who delivered the condemned. It is I who gave life to the dead.

It is I who raised up the buried. Who will argue with me?

It is I, says Christ who destroyed death. It is I who triumphed over the enemy,

And trod down Hades, and bound the strong man,

And have snatched mankind up to the heights of heaven. It is I, says Christ.

So then come here all you families of men, weighed down by your sins.

And receive pardon for your misdeeds. For I am your pardon.

I am the passover which brings salvation. I am the lamb slain for you.

I am your lustral bath. I am your life. I am your resurrection.

I am your light, I am your salvation, I am your king.

It is I who bring you up to the heights of heaven.

It is I who give you resurrection there.

I will show you the eternal Father. I will raise you up with my own right hand.4

Prophecy since the third century

It is clear that since the third century prophecy has been neither continuously manifest in particular churches, nor common to the whole church at any one time. There have been, however, regular recurrences of prophetic activity in the history of the Christian people, most commonly in certain movements of renewal. In such movements, prophecy did not occur as an isolated spiritual phenomenon, but rather as an element of a broader manifestation of “charismatic” power. Healings, miracles, inspired preaching, and other “charisms” were all witnessed by the participants in these renewal movements.

The first, and most outstanding, of these movements was the ascetic movement which swept through the whole church, particularly in Egypt and Asia Minor, during the fourth, fifth, and sixth centuries. There are numerous accounts of healings, prophecies, exorcisms, and miracles in the histories of this movement (see Palladius, The Lausiac History, Athanasius’ Life of Antony, the Historia Monachorum, the histories of Socrates and Sozomen, etc.).5 The movement maintained a high degree of vitality for two centuries and culminated, in the West, in the Benedictine movement (of Benedict there are again miracles and prophecies recorded) and in the East in numerous monasteries.

Perhaps the most outstanding prophet of this period was John of Lycopolis. His prophetic powers were attested by Palladius, Sozomen, Augustine, Cassian, and the Historia Monachorum.6 Palladius, for instance, says that John “was deemed worthy of the gift of prophecy Among other things, he dispatched various predictions to the blessed emperor Theodosius in regard to Maximus the tyrant, that he would conquer him and return from the Gauls.” John also prophesied that Palladius’ brother had been “converted” and that Palladius himself would become a bishop. All this proved true.7 Sozomen records that John correctly prophesied the deaths of Theodosius and Eugenius.8

Numerous other ascetics possessed the gift of prophecy, or at least prophesied at one time or another (for example, Didymus,9 Marcarius of Egypt,10 and Isidore”11). The ascetics considered the gift of prophecy to be a great blessing, but not an unexpected one for people who sought to follow God.

A second movement of renewal involving similar charismatic activity swept through the Western church in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The Cistercian movement, which arose in France during the twelfth century, and the Franciscan and Dominican movements, beginning in Italy at the start of the thirteenth century, wrought a massive change in the Western church. All three of these movements (which appeared as components of a broader movement of the time) were accompanied by prophecy, healing, miracles, and other manifestations of charismatic activity.12

Other major and minor movements of renewal in the church among the Christian people could be included in such a review of prophetic activity (for example, the Hesychasts in the East, and even the American “Second Great Awakening”).13 There have, of course, been many other incidents of prophecy, either manifested in the life of a particular individual or in groups of people for short periods of time. But, taken as a whole, the history of prophecy since the third century is characterized primarily by movements of renewal which exhibited a wide variety of charismatic activities.

In the twentieth century this phenomenon has been repeated in “pentecostal” and “charismatic” movements originating in the United States in the first decade of the century and increasing in size and scope over the last seventy years. At the present time this movement comprises well over twenty million people in “Pentecostal” denominations, hundreds of thousands of persons in the Orthodox and Protestant churches, an indeterminate number in “independent charismatic” congregations, and perhaps as many as twenty million Roman Catholics.

Two observations about prophetic activity in Christian history

There are two observations worth making about prophetic activity since the early days of the church. The first is that it mainly resurfaced in the context of a broader revival of charismatic gifts. That is not at all surprising, since Paul treats such gifts as prophecy, healing, and miracles (for example, 1 Corinthians 12) as basically one type of gift. Where charismatic activity is prevalent one should not be surprised to see it take many forms.

The second observation is that prophecy and other charismatic gifts flourish in an atmosphere of expectant faith. That is, they operate mainly where they are expected by those who receive them. Healing occurs most often when people believe that healing is possible. Francis of Assisi, John of Lycopolis, and Bernard of Clairvaux all expected that God would speak to them. And he did.

Prophecy has at times come into disrepute through abuse. The theory that prophetic activity disappeared gradually in the third century in reaction to some abuses may be accurate. As a result of various heterodox “prophetic” movements—some of which are with us today—Christians have developed considerable reservation in regard to prophetic activity.14 While in the early church prophets were held in honor15, they have since become more and more subject to suspicion. But if God does bestow the prophetic gift upon the church, then we should be able to receive it. I recently read a statement which summarizes well the attitude we should maintain: “As soon as we speak of prophets, people are immediately worried about false prophets. On the contrary, it seems to me that we should pray for prophecy! The problem now is an absence of prophets. It seems that the Holy Spirit is raising up prophets in our midst. We should be attentive. The community can judge the worth of prophecy after it happens, but let it happen first.”16

There were false prophets even in the times of the New Testament (for example, 1 John 4:1), but Christians were taught how to handle them (1 John 4, Didache 11:7-12). The presence of false prophets did not prevent Christians from recognizing and receiving those who were genuine. In fact, toward the end of the second century, Irenaeus of Lyons wrote a strong denunciation of Christians who wished to suppress prophecy on the grounds that it could possibly be false:

Others, again, that they might set at naught the gift of the Holy Spirit, which in the latter times has been, by the good pleasure of the Father, poured out upon the human race, do not accept that gospel of John in which the Lord promised that he would send the Paraclete; but set aside at once both the gospel and the prophetic spirit. Wretched men indeed, who in order not to allow false prophets set aside the fits of prophecy from the church; acting like those who, on account of such as come in hypocrisy, hold themselves aloof from the communion of the brethren. We must conclude, moreover, that these men cannot admit the Apostle Paul either. For in his epistle to the Corinthians, he speaks expressly of prophetical gifts, and recognizes men and women prophesying in the church. Sinning, therefore, in all these particulars, against the spirit of God, they fall into irremissable sin.17

The early church had faith that if God gave gifts to his people, he would also provide them the means to safeguard the exercise of those gifts. Prophecy is reappearing in the church today. We need the confidence that we can both benefit from its power and guard against its abuse.

1. I am inclined to the view that Paul here refers to prophets in the New Testament church and not simply to those of the Old Covenant.

2. Justin, Dialogue with Trypho, in Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. I (New York: The Christian Literature Co., 1890), 240 (Chapter LXXII).

3. Irenaeus, Adversus Haereses, Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. I (New York: The Christian Literature Co., 1890), 532.

4. Othmor Pevlev, ed., Meliton De Sardes: Sur La Paque et La Paque el Fragments (Paris: Les Editions du Cerf, 1966), 122. English translation in Michael Green, Evangelism in the Early Church (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1970), 201-202.

5. Palladius, Lausiac History, trans. Robert T. Meyer, Ancient Christian Writers, no. 34 (Westminster, Md.: Newman Press, 1965); Athanasius, Life of Antony, Early Christian Biographies, Fathers of the Church, Vol. 15 (New York: Fathers of the Church, Inc., 1952), 125-216; Historia Monachorum, The Paradise of the Fathers, trans. E. Wallis Budge (London: Chatto and Windus, 1907); Socrates, Ecclesiastical History and Sozomen, Ecclesiastical History, A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series, vol. II (New York: The Christian Literature Co., 1890).

6. Palladius, Lausiac History, 98-103, Sozomen, Ecclesiastical History, 392. Augustine, De cura pro mortuis gerenda ad Paulinum episcopum17, Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum (41.655); Casian, Conferences (24.26) and Institutes (4.23-26), A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series, Vol. XI (New York: The Christian Literature Co., 1890), 545, 226-27. Historia Monachorum, chapter two.

7. Palladius, Lausiac History, ch. 35; Sozomen, Ecclesiastical History, VI, 28.

8. Sozomen, Ecclesiastical History, VII, 22.

9. Palladius, Lausiac History, IV.

10. Palladius, Lausiac History, XVII.

11. Palladius, Lausiac History, IX, 10.

12. See for instance, on the Cistercians, W.W. Williams, St. Bernhard of Clairvaux (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1935), 275; on (Garden City, New York: Image/Doubleday, 1958), 96-99, 130-31, Omnibus of Sources, ed. Marion Habig (Chicago: Franciscan Herald 1973), 711-20; on the Dominicans, Bede Jarret, Life of St. Dominic (Garden City, N.Y.: Image, 1924), 87, 118, and Henri Gheon, St. Vincent Ferrer (New York: Sheed and Ward, 1954), 108, 115.

13. The history of hesychasm in the Eastern church is not actually that of a clearly defined movement. Rooted as far back as the fourth-century ascetic movement, it became a significant spiritual force in the East, especially between 1000 and 1453. While certain elements of hesychasm do not lend themselves to extensive prophetic activity, manifestations of prophecy can be found in the lives of different Greek and Russian hesychasts, most notably St. Symeon the New Theologian. See George Maloney, The Mystic of Fire and Light(Denville, N.J.: Dimension Books, 1975), 73, 170-71. For an example fro m the “Second Great Awakening” see Charles Finney, Charles G. Finney: An Autobiography (Old Tappen, N.J.: Fleming H. Revell, 1876), 114-22.

14. E.G. KarlRahner, Visions and Prophecies (New York: Herder and Herder, 1963). Rahner is rather skeptical of visions and revelations — and produces good evidence of the reasonableness of his position. I think that, though Rahner recognizes the distinction between “mystical revelations” and charismatic prophecy, he does not really treat charismatic prophecy in his book. His criteria for discernment do not apply to gifts of prophecy. The book does give a good picture of the grounds for distrust of some revelations, however.

15. Cf. Ephesians 2:20, Didache 10:7, 13:1, etc.

16. Joseph Hogan, “Charisms of the Holy Spirit,” Restoration, March 1972, 8.

17. Adversus Haereses, III, 11, 9.

This article is excerpted from Prophecy: Exercising the Prophetic Gifts of the Spirit in the Church Today, Chapter 1, by Bruce Yocum, © 1976, 1993 The Servants of the Word. Revised edition published in 1993 by Servant Publications.

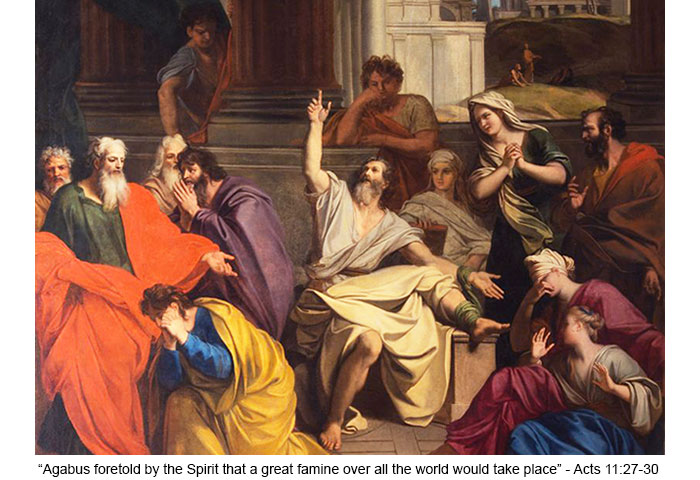

Top image credit: The prophet Agabus delivers his prophetic message to Paul the Apostle, painted by Louis Chéron, a French artist, in 1687. Image in the public domain.

Bruce Yocum (1948 – 2022) was involved in leadership and teaching for many years in the Catholic Charismatic Renewal and the Covenant Communities Movement which began in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and in the Sword of the Spirit. He travelled widely throughout the Sword of the Spirit communities to equip and train community leaders in North America, Europe and the Middle East, Latin America and the South Pacific. Bruce Yocum was a life-long member of the Servants of the Word, an international ecumenical brotherhood of men living single for the Lord. He served as Presiding Elder of the Servants of the Word for thirteen years (1989-2003).

I thought I was a cessationist but the more I have studied into the topic, I believe that what has been going on is a church-wide quenching of the Spirit and His gifts. There are no “credible” churches that I know of that adhere to anything in 1 Cor 14. Why is this? Why is there not a part of the church who legitimately try to follow that section of scripture? Why have we instead morphed to a single pastor that acts as a sort of “life coach”? The majority of mainstream churches boil down to that. Have the prophets of 1 Cor 14 become silenced in favor of only a teacher? Why? How do we change this and where can I go to join a church that hasn’t turned this into a theatrical show?

I am a prolific writer of Christian poetry that has often proven prophetic. For twenty one years I have been sharing a painful, convicting yet hopeful message of a great revival to come embodied in three poems written about 9-11 beforehand. I am a dumb sheep, just ask my wife, who manages to follow God’s leading with an attitude of willing obedience, though not 100% admittedly.

I have observed genuine miracles following an initial ‘road to Damascus’ encounter. This means I failed miserably early on and had a hardened heart and seared conscience unreachable by standard practice. It took extraordinary grace to pull this prodigal out of the pig trough.

I was given an unusual gifting bestowed in a remarkable way and walked through severe spiritual warfare in the early days. I was remarkably immature. Still growing up. Just ask my wife. Maybe not. Just being transparent.

I experienced all the gifts as part of my training to better understand their function. But the prophetic twined with and through the artistic seems to be the dominant characteristic. The gift of administration seems to have escaped my grasp. Ouch!!

The Lord has definite plans for a major impacting revival. He’s working on various participants even as you read this. Assuming you do.

Happy to share what I refer to as the 9-11 message. I do it often. Just planting seeds. I have many other messages as well. God can provide an endless supply to those who will scatter what He provides.

His seeds don’t have to be dressed in poetic phrases. Just ask any mechanic willing to donate time and expertise to a single mom struggling to keep her car running for transportation to a critical work schedule. You get the idea.