The brothers and sisters who started Christian communities discerned a call to live in community, but in the beginning, they did not know what that would mean. The forms of community life developed over the course of many years, with many experiments, both successful and unsuccessful. The formation of community was a costly process. It involved great effort and often pain. Human nature, always prone to sin and error, had to be reckoned with. People living in close relationship with one another rubbed away many of the sharp edges of personalities. It was only by the grace of God through the working of the Holy Spirit that Christian community could develop. Even then, many attempts at building community failed – probably many more than succeeded. That covenant communities exist and flourish today is a testimony to the work of God and the dedication of many who died to self and dedicated themselves to following his call as well as they could discern it.

Steve Clark’s 1972 book Building Christian Communities: Strategy for Renewing the Church was the first systematic exposition of the principles behind the vision that covenant communities came to embody.[1] In it, he describes the importance of environment for forming individuals and argues that since the larger modern social environment is not conducive to Christian living, environments must be constructed to counteract its influence. What the Church needs, he argues, is “basic Christian community.” He defines it as follows:

A basic Christian community is an environment of Christians which can provide for the basic needs of members to live the Christian life. As such it is the smallest self-sustaining unit of Christian living. In it, its members can find on a regular basis all they need for living the Christian life.[2]

Steve Clark’s book is not specifically aimed at the charismatic renewal. In fact, the book was written for the Cursillo movement and draws on the experience of efforts at Catholic Church renewal in Latin America, as well as the call of the Latin American Catholic bishops for basic Christian community in the documents of their conference in Medellín, Colombia, in 1969. It does, however, also draw on the experience and example of the emerging community in Ann Arbor. Clark also mentions charismatic renewal as one of the movements that he sees as resources for building community.

A Christian community, he says, is a special kind of environment. First, it must consist of people who have a personal commitment to Christ. As an environment, it must be “relationship-oriented and not just task-oriented.” It must also be a large enough group to provide what is needed by its members, and in a small enough geographical area that relationships can be maintained. In addition to these characteristics, it must have organization and unity, and be concerned with “all that is involved in being a Christian.”[3]

He goes on to describe some of the characteristics of organization but focuses chiefly on the need for a new kind of leadership: leaders who can take an environmental approach. He says that “the Church needs men of God, then, men who are committed to Christ above all and who are willing to work to bring others to a commitment to him. They must be spiritual men, men who know God, and who can lead others to know him.”[4] He further argues that the community, while it requires organization and leadership, is also concerned with relationships and with the whole of the Christian life. What he calls “full community” characterized the community of the first Christians.

Early years of developing full community life

Most groups within the Church, he says, including “communities that have developed from the Cursillo movement or the Charismatic Renewal” are limited communities, since only a part of the member’s life is of concern to the community. The leaders who founded The Word of God and other covenant communities, however, envisioned them as “full” communities in the sense described in Building Christian Communities. It was one thing, however, to describe the goal of full community, and quite another to live it out. It took many years to work out what kind of life a full covenant community should have. The first generation of community members had to work through many changes and painful choices in the development of community life.

In order to be more than an informal environment, a basic Christian community requires organization. Much of the organizational model of covenant communities like The Word of God derived from the Cursillo movement. The community gathering and small groups, both of which figure in Building Christian Communities, mirror the Cursillo ultreya and grupo. These elements may, however, take various forms, as the history of The Word of God illustrates.

Public commitment of members to the community covenant

The earliest element of organization in the Ann Arbor community was the adoption of a definite commitment to the community. Such a defining of membership developed from simple participation in the Monday prayer meetings after the 1969 retreat at Camp Takona, The Word of God’s leadership grew from the original four men into a larger council that guided community activities. In a report in April 1969, we can see that determining membership in the community is simply a matter of looking at a list of names kept by one of the leaders.[5] A year later, the report can describe a process for becoming a member of the community, and the number of members can be given precisely.[6]

It is interesting to note that with the adoption of a name at the 1970 conference, The Word of God also adopted a structure. The commitment to the community became a public declaration, “I want to give my life fully to God and live as a member of The Word of God.” The commitment was deliberately phrased so that it could not be taken for a formal vow in Catholic usage, but a statement of intention to accept the terms of the covenant of the community.

After the first two groups had made the public commitment in September and November of 1970, the community introduced the “underway” status for those who were approaching full membership. The underway commitment, which was originally made privately to a community leader, was a statement of a decision to live according to the community covenant on a temporary basis but without the firm commitment implied by public commitment. The public commitment and the underway commitment have remained features of many communities, including those in the Sword of the Spirit. In addition, the term “underway” has also become a term for a tentative working commitment between communities.

Adapting New Testament patterns of Christian community life and service

The structure of the new community was designed to imitate the structure of the early Church as depicted in the New Testament. Early documents speak of “elders,” “deacons,” and “deaconesses,” although the leaders decided against these terms, as they suggested an attempt to start a separate church. Instead, the leaders who governed the community were called “coordinators,” a term that had been in use in much of the apostolic work of the team in Ann Arbor and among other renewal groups at the time. It suggested that their function was to “coordinate” or organize the work of other leaders, but the description of their work went beyond that. They were also charged, as a group, with overall responsibility for the life of the community and with training others to be leaders. The coordinators were assisted by “servants” who did administrative work for the coordinators, and “handmaids” (now called “senior women leaders”) with a special responsibility for the care of women, under the direction of the coordinators.

Community sub-groupings and growth groups

The 1970 report describes “sub-communities” within the community, that is, informal groupings of members. These include groupings in University of Michigan dormitories and geographical groups. Besides the “sub-communities,” the report describes “living groups,” that is, people living together in the same house or apartment.[7] It also describes “growth groups,” or small groups that “follow the format of the Cursillo group reunion.”[8]

With the formalization of community structure in 1970, sub-communities became defined, generally geographical, groups within the community. There were originally four sub-communities; three of them, mostly comprising students, led by two coordinators each. The Monday community gatherings were mostly held by sub-community, with occasional – initially monthly – gatherings of the entire community. The Thursday night open prayer meetings continued as well for the community as a whole.

The principal reason for sub-communities was the conviction that the basic community unit had to be small enough that people would know one another, at least by sight. While Steve Clark in Building Christian Communities considers that a “basic pastoral unit” may be as large as 1000, with a normal size of 500,[9] he usually thinks of groups of around 200.[10] By September 1971, The Word of God included 349 underway and publicly committed members.[11] With nine sub-community coordinators, this meant there were almost thirty-eight members per coordinator, which corresponds roughly to the upper limit of forty for what Clark calls a “small group” where everyone can know the others.[12] As The Word of God grew, the sub-community structure changed, responding to growth in numbers and changes in demographics. By 1990, when the community had over 1000 adult members, its twelve districts were grouped into three branches, which functioned to some extent as subordinate communities.

Household units

In the beginning, the most basic unit of The Word of God in the beginning was the household. Households originally were groups of single people living together in one house or apartment. It also became the smallest pastoral unit of the community, with one member being pastorally responsible for the other members. By September 1971, households had become “the basic unit in the life of the community.”[13] Some were formed as married couples took single people into their homes, other “households” in dormitories were formed as groupings of people living in student housing, and a new development, “non-residential households,” provided small groups for individuals or couples living by themselves. As the community grew, households consisting of a married couple and their children along with several single men and women became more common. The growth of households of this kind was encouraged by the example of similar households in the Church of the Redeemer, a charismatic Episcopal parish in Houston, Texas.[14] In many cases, including most households led by married couples, the members of the household received pastoral care from the husband in the family. In other cases, the pastoral leader for the members of the household was often someone outside the living situation.

Men’s and women’s groups

In the summer of 1977, the community began to move from the household as the basic unit to men’s and women’s groups, generally each with at least four and fewer than ten individuals. Most of these comprised people of the same state in life and roughly the same age. The new groups were inspired by the “cell groups” that had formed in the People of Praise community in South Bend, Indiana. As the large households that had characterized the early 1970s began to dissolve – often because the growing families had less room for unrelated singles – men’s and women’s groups seemed to fit the situation better. In a way, these small groups represented a reversion to the model of the Cursillo group reunion that had characterized the community at the beginning. Ever since, these groups have been the basic unit of communities in the Sword of the Spirit.

Brotherhood of men living single for the Lord within covenant community

In the early 1970s, the development of a celibate brotherhood of single men within the community was a turning point in community life and outreach. When Steve Clark, Ralph Martin, Jim Cavnar, and Gerry Rauch came to Ann Arbor in 1967, they were all single men, and saw themselves as, at least for a time, fully dedicated to Christian service. The rest of the team who joined them in 1968 consciously took the same approach, not least because, as full-time apostolic workers, they had, for financial reasons, to live very simply. Ralph Martin married in 1968, Jim Cavnar in 1969, and Gerry Rauch in 1972. However, several men who became leaders in the community (including six of the original eleven coordinators) had felt called to a life of celibacy – of “living single for the Lord,” to use their preferred term. Most of them lived in a household with Steve Clark, first at 500 Packard Street and later at 335 Packard Street, where they would meet to study various historical rules for celibate community life such as those of St. Francis of Assisi, St. Basil the Great, and St. Benedict.

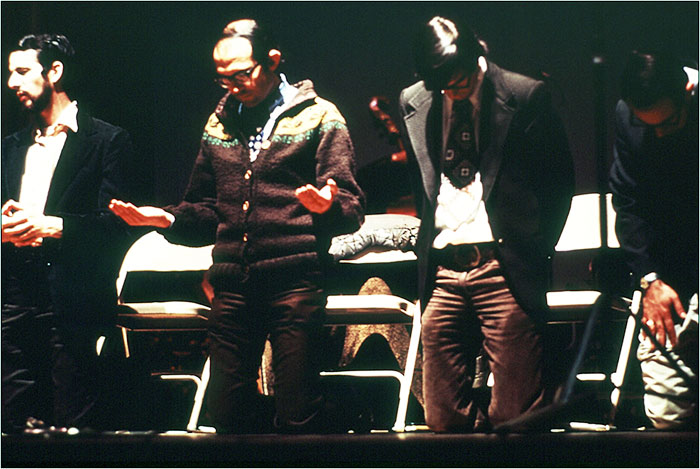

At Pentecost 1971, Steve Clark and seven other men made a temporary commitment to live “single for the Lord” for one year. Later that year they developed a statement of their commitment and way of life, their “covenant,” and began to live together as a brotherhood. Several of the men decided to leave after the initial commitment expired, but five men continued, and other men who were attracted to the ideals of their life joined them.

In January 1974, Steve Clark and four other men made a lifelong commitment to live single for the Lord in the brotherhood, a commitment repeated in a public ceremony in February. More brothers joined; in September of that year, there were two households of men in the brotherhood. In January 1976, they received a name: The Servants of the Word. While the first brothers were Catholics, they had always intended to be open to Protestant and Orthodox brothers. The first Protestant brothers began to make commitments in late 1975.

In August 1976, Steve Clark and a household of Servants of the Word moved to Belgium to work in international outreach; the household later moved to London. A house was started in Manila in the Philippines in 1982. The Servants of the Word have grown as a worldwide brotherhood ever since, now with houses in the United States, the United Kingdom, Mexico, Costa Rica, the Philippines, and Lebanon, and they have often spearheaded new outreach ventures in the Sword of the Spirit.

Ecumenical concerns and decision to identify as an ecumenical community

The larger Word of God, like the Servants of the Word, had to deal with the ecumenical issue. The initial work of the men who came to Ann Arbor centered around St. Mary’s Catholic Student Chapel and the associated Newman Center. The work was focused on renewing the life of Catholic students. The prayer meeting group they began, and the associated groups in other places, were part of the Catholic charismatic renewal and worked within that movement. Steve Clark’s Building Christian Community specifically addresses the renewal of the Catholic Church and envisions a Eucharistic celebration as part of normal community activity.[15] From the beginning of The Word of God, however, Protestant (and occasionally Orthodox) Christians participated in prayer meetings and in community life.

The Catholic identification of the community continued after the organization of the community in 1970. Originally, there were Catholic Eucharistic celebrations for the various sub-communities and for community gatherings.[16] One result of this combination of community meeting and Mass was that many Protestant members received Communion at the Mass, although the community leaders did not encourage this, as it was contrary to Catholic practice. The leaders of the community first went to the pastor of the student parish about this issue, he reminded them not to allow non-Catholics to receive Communion. The local Catholic bishop, moreover, advised them to become officially an ecumenical group. Therefore, in November 1971 the coordinators decided to discontinue having Catholic Eucharists in connection with community meetings, and to adopt the identity of an ecumenical community.[17]

The term “ecumenical” has always been preferred to alternative terms such as “nondenominational” or “interdenominational.” It indicates, first, that members of the community do not give up their connection to a Christian church body. In fact, the practice of The Word of God at that time, and of other covenant communities, has been to encourage members to be active participants in their churches. Secondly, the term “ecumenical” indicates that the members of the community enter into the covenant relationship as individual Christians, recognizing their fellow members as brothers and sisters in Christ, rather than as representatives of a church or Christian tradition. The community set an explicit standard of belief in the doctrines expressed in the Nicene Creed, but was always careful to teach in a way that would be acceptable to Christians of all traditions.

Connecting communities with wider church bodies

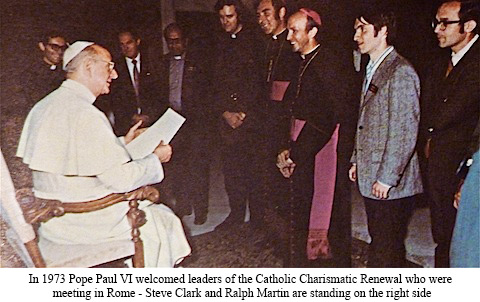

Beginning in 1973, as the charismatic renewal spread throughout the world, the leaders of covenant communities, especially Ralph Martin and Steve Clark, began to explore ways of connecting what God was doing in communities with the wider Catholic Church. At a series of meetings in Rome with Vatican officials, they began to consider having a formal organization for Catholics within the ecumenical life of The Word of God. The community had good relations with the local Catholic bishop (after 1970, the bishop of Lansing) and these discussions continued with Bishop Alexander Zaleski until his death in 1975, and with his successor, Bishop Kenneth Povish. Both bishops supported this plan as it took shape.

Over the course of the 1970s, Christians from different traditions joined the community and some assumed positions of leadership. The coordinators therefore sought to provide some way in which the Protestant members of the community could relate to their own traditions in the context of community life. With the idea of a Catholic grouping as a model, they conceived the idea of groupings for Protestants. In July 1976, the coordinators began to discuss formally the idea of having “fellowships” – groupings that would serve as a Catholic parish and as local congregations for the Lutheran, Reformed, and Free Church traditions. In September 1977 this idea was proposed to the community in a consultation and approved by the membership two months later.

At first the coordinators, concerned about the effect the new Catholic fellowship would have on local parishes, favored only some of the Catholics joining it. Bishop Povish, however, asked that all Catholics in the community be included. Two years passed as the fellowships were organized and pastors were found for them, and in June 1981, the fellowships began to function. The four fellowships that formed are now independent churches: Christ the King Catholic Church (a non-territorial charismatic parish in the Diocese of Lansing), Covenant Community Church (Evangelical Presbyterian), Cross and Resurrection Lutheran Church (Missouri Synod), and two churches in the Vineyard network. While many community members belong to them, they also have many members who have never belonged to covenant community. In this way, not only charismatic life, but also many of the principles learned in community, have been passed on to a wider body of Christians.

Common patterns of prayer and celebration of the Lord’s Day

Starting with the Servants of the Word, The Word of God began to develop shared patterns of prayer, and these were adopted by many families and individuals in the community. The most important of these was the ceremony for setting apart Sunday as the Lord’s Day, developed in the late 1970s by the Servants of the Word and spread to other households from there. In November 1980, The Word of God coordinators had the ceremony published, along with a set of daily family prayers, and asked members of the community to use these in their homes. Along with the ceremony, teachings were developed about the significance of keeping the Lord’s Day holy, free from “weekday thoughts and cares.” The coordinators also began to encourage the observation of the seasons of Advent as a preparation for Christmas, and of the Forty Days (Lent in many churches) leading up to the feast of Easter. Community gatherings during these seasons had special themes to observe these Christian seasons. This concern for the weekly and annual rhythm of life, and particularly the making special the Lord’s Day, remain an important feature of life in the Sword of the Spirit.

The coordinators of The Word of God were from the beginning concerned with the development of leaders. Not only was there a need for training and establishing more coordinators to take overall responsibility for the community as a body; within each sub-community, the household heads assumed pastoral responsibility for the members of their households. As the community grew, more men and women were trained as leaders to take responsibility for the new people who were coming in. In residential households, the head of the family was considered the “head” of those in the household in the way that, as husband and father, he would be head over his wife and children. The authority of the head extended to the residents’ participation in household life. In other respects, the head of the household – and by extension heads in non-residential situations – acted as the representative of the coordinators.

From the beginning, the coordinators defined their authority in terms of the areas in which the individual member of the community was expected to follow their lead. In areas related to participation in the community they expected full cooperation. These areas included attendance at community gatherings, respecting the “pattern and order” of community life, and contributing financially to the community. As regards other matters in the personal life of the member, such as occupation, choice of a state in life, or direction of studies, the existence of the covenant bond meant that the advice of the coordinators should be taken seriously, but obedience was not required. As the community evolved over the years, the pattern of “headship” changed several times. In November 1983, the coordinators decided that the term “head” was inappropriate to the relation that they intended to exist. The term “pastoral leader” was introduced instead. The pastoral leader, they reasoned, was not the head of another man or woman as Scripture intended a husband to be head of his wife and family.

Along with pastoral leadership, the coordinators were heavily engaged in teaching. Even before The Word of God was organized, the Foundations in Christian Living course (Foundations Course I) was part of joining the community. By 1971, Foundations in Christian Living II, with separate sections for married couples, single men, and single women, was added to the body of community courses that formed the process of formation for underway members. These came very early. Other courses were added: Emotions in the Christian Life (originally “The Christian and His Emotions”), Fruit of the Spirit, Christian Personal Relationships, and Living in Christian Community among them. In addition, there were other times of teaching, for example, Parents’ Forums for teaching on family life, and special training for pastoral leaders.

In the course of developing the teaching to be given to members of the community, the leaders of the community had to confront a number of social trends that were in conflict with Christian teaching. The Foundations Courses had to deal with areas of sexuality where traditional Christian teaching on chastity was being openly flouted by the sexual revolution. More broadly, the trends in society tending toward a focus on individual self-development conflicted with the Christian ideal of death to self in the service of others. A tendency to distrust any kind of authority conflicted with the acceptance of the authority of Scripture as well as church and community leadership.

Men’s and women’s roles and raising families

Probably the most challenging area that emerged concerned the roles and identities of men and women. This affected family life, child-rearing, and community life. The leaders of The Word of God, and other covenant communities as well, became concerned with the erosion within society of the distinction of the sexes, the feminization of men, and the masculinization of women. This especially affected the roles of mothers and fathers in forming boys and girls to be Christian men and women. Steve Clark’s Man and Woman in Christ, published in 1980, was an extensive study of the question, discussing in depth both the scriptural teaching on the subject and the findings of research in the social sciences. As Clark explained it, the work originated mainly in a concern for family life and identity: “This is not a book on the political issues raised by the feminist movement…. If there was any issue that gave rise to the ideas in this book, it was the issue of raising children. What are we to say to children about the fact that they are girls and boys? How are we to teach them to relate to their maleness and their femaleness?”[18]

In spite of its nuanced conclusions relating to occupations and ordination to ministry, among other questions, the book confronted directly much of the feminist approach to biblical interpretation and social theory. Therefore, it could not help but arouse some controversy. The book does not prescribe strict rules but presents in a general way an interpretation of the New Testament teaching on the roles of men and women. Beyond the principle that husbands are the heads of families and that men should be the overall leaders in Christian communities, it leaves a great deal of flexibility to specific social situations.The teaching on men’s and women’s roles was part of a larger stream of teaching that became part of community life. This teaching also included such areas as child-rearing, the showing of respect and honor, and use of entertainment and media. The goal was to build a community that could function as a new society different from the surrounding society but within it. Many of these principles are still taught in communities belonging to the Sword of the Spirit.

[1] Stephen B. Clark, Building Christian Communities: Strategy for Renewing the Church (Notre Dame, IN: Ave Maria Press, 1972).

[2] Clark, Building Christian Communities, p. 70. Emphasis original.

[3] Ibid., pp. 70-71.

[4] Ibid., p. 110.

[5] [Stephen B. Clark], “Pastoral Report on the Catholic Pentecostal Community in Ann Arbor” [Summer 1969], p. 3.

[6] [Stephen B. Clark], “Pastoral Report on the Catholic Pentecostal Community in Ann Arbor” April 1970, pp. 2a-3.

[7] [Clark] 1970, pp. 8-10.

[8] Ibid., p. 10.

[9] Clark, Building Christian Communities, p. 74.

[10] E.g., ibid., p. 76.

[11] [Stephen B, Clark], “Pastoral Report on ‘The Word of God,’ a Charismatic Community in Ann Arbor,” September 1971, p. 3.

[12] Clark, Building Christian Communities, p. 72.

[13] [Clark] “Pastoral Report…1971”, p. 6.

[14] Church of the Redeemer and its households were discussed in several articles in New Covenant 1:6 (December 1971): Jerry Barker, “God’s Transforming Power,” pp. 1-5, and “Families and Community Life,” pp. 6-8; Owen Barker, “Experience of a Son,” pp. 9-10; and Fr. Graham Pulkingham, “Marriage, Community, Service,” pp. 11-14. See also Fr. Graham Pulkingham, “A Church Reborn” New Covenant 4:3 (September 1974), pp. 34-36.

[15] Clark, Building Christian Communities, p. 77

[16] [Clark] “Pastoral Report…1971,”, p. 5 mentions subcommunity Eucharists. Eucharistic celebrations for the whole community are not mentioned here, but they happened as well.

[17] “History of The Word of God,” (The Word of God archives).

[18] Stephen B. Clark, Man and Woman in Christ (Ann Arbor: Servant Books, 1980), p. x.

This article © 2021 The Sword of the Spirit is adapted from A Brief History of the Sword of the Spirit, by Bruce Yocum, Bob Bell and Henry Dieterich, commissioned by the International Executive Council of the Sword of the Spirit to mark the 50th anniversary of covenant community.

Photo credits: © Sword of the Spirit, Word of God, and Living Bulwark archives 1967-2021

This is part of the series: A Brief History of the Sword of the Spirit

- Bruce Yocum, leader of the writing team, and author in his own right, was part of the communities movement since 1968 and held various leadership roles for more than 50 years. He was instrumental in the formation and growth of numerous communities in the Sword of the Spirit.

- Henry Dieterich has been present in Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA, for most of the time since the beginnings of the communities movement. He holds a doctorate degree in history from the University of Michigan and did most of the actual writing of the history, fostering a rigorous standard of historical research and accuracy. Henry lives in Ann Arbor with his wife Roz and is a member of Word of Life there, a community of the Sword of the Spirit.

- Bob Bell was also present in Ann Arbor for decades, starting in the autumn of 1967 and an eyewitness to much of the early history of the Sword of the Spirit and the communities movement. He was also part of the start-up team for Jerusalem, the Sword of the Spirit community in Belgium. He works for the Sword of the Spirit administrative and editorial staff and has made his home in London, England, and is also part of Antioch, a member community of the Sword of the Spirit.