Christ

heals the sick. On the very

pages of the Gospels he appears as the

healer. He had hardly begun his

teaching when the sick started coming.

They were brought to him from every

quarter, It was as if the masses of the

afflicted were always opening up

around and closing in on him. They carne

by themselves, they were led,

they were carried, and he passed through

the suffering multitude of people,

and "a power from God was present, and

healed" (Luke 5:17)....

At

times, one is prompted to look

behind the outward events at the inner

working of this sacred power.

A

blind man came to him. Jesus put

his hands on the man's eyes, drew them

away, and asked, "What do you see?"

All overcome with excitement, the man

answered, "I can see men as if they

were trees, but walking!" The healing

power reached into the nerves. They

were revivified, but they did not yet work

properly. So he put his hands

on the eyes once again, and the man saw

things as they were (Mark 8:23-25).

Does not this story give one a sense of

experiencing the mystery, as it

were, from behind the scenes?

Another

time, there was a great crowd

about him. A woman afflicted many years

with a hemorrhage, who had sought

everywhere in vain for a cure and had

spent all her money to find one,

said to herself, "If I can even touch his

cloak, I shall be healed." And

she came up to him from behind, touched

his garment, and noticed in her

body that the distress which had been

plaguing her for so long was at an

end. But he turned around: "Who touched my

garments!'" 'The Apostles were

dumbfounded: "Can you not see the

multitude pressing so close about you,

and yet ask, 'Who touched me?'" But he

knew just what he was saying; immediately

he had been "inwardly aware of the power

that had proceeded from him."

And the woman came up to him trembling,

threw herself at his feet, and

confessed what had happened. But he

forgave her freely and lovingly (Mark

5:25-34; Luke 8:43-48).

What an

effect that had all around!

He seemed charged with healing, as if he

needed no intention. If someone

approached him in an open-hearted,

petitioning state of mind, the power

simply proceeded from him to do its

work.

The open road

back to God

What did the act of healing mean

to Christ? It has been said that he was the

great friend of mankind. Characteristic

of our own time is an extremely alert sense

of social responsibility and

responsiveness to works of mercy. So there

has been a corresponding desire

to see in him the towering helper of men,

who saw human suffering and,

out of his great mercy, hastened to relieve

it.

But this

is an error. Jesus is not

a personification of the big-hearted

charitable nature with a great social

conscience and an elemental power of

helping others, going after human

suffering, feeling its pangs in sympathy,

understanding it, and conquering

it. The social worker and the relief

worker are trying to diminish suffering,

to dispose of it entirely, if possible.

Such a person hopes to have happy,

healthy people, well-balanced in body and

soul, live on this earth. We

have to see this to understand that Jesus

had no such thing in mind. It

does not run counter to his wishes, but he

himself was not concerned with

this. He saw too deeply into suffering.

For the meaning of suffering, along

with sin and estrangement from God, was to

be found at the very roots of

being. In the last analysis, suffering for

him represented the open road,

the access back to God-at least the

instrument which can serve as access.

Suffering is a consequence of guilt, it is

true, but at the same time,

it is the means of purification and

return.

He took our sufferings

upon himself

We are

much closer to the truth

if we say Christ took the sufferings of

mankind upon himself. He did not

recoil from them, as man always does. He

did not overlook suffering. He

did not protect himself from it. He let it

come to him, took it into his

heart. As far as suffering went, he

accepted people as they were, in their

true condition. He cast himself in the

midst of all the distress of mankind,

with its guilt, want, and

wretchedness.

This is

a tremendous thing, a love

of the greatest seriousness, no

enchantments or illusions-and therefore,

a love of overwhelming power because it is

a "deed of truth in love" (Ephesians

4:15; 1 John 3:18), unbinding, shaking

things to their roots.

Once

again we must see the difference:

He did this, not as one carrying on his

shoulders the black tragedy of

the human condition, but rather as one who

was to comprehend it all, from

God's point of view. Therein lies the

characteristic distinction.

His healings reveal

the living God

Christ's

healing derives from God.

It reveals God, and leads to God.... By

healing, Jesus revealed himself

in action. Thus he gives concrete

expression to the reality of the living

God. To make men penetrate to the reality

of the living God-that is why

Christ healed.

[This excerpt is from the

book, The Inner Life of Jesus,

by Romano Guardini, originally published

in German, Jesus Christus,

geistliches Wort, 1957. English

translation

copyright © 1959 by Regnery Publishing,

Inc.]

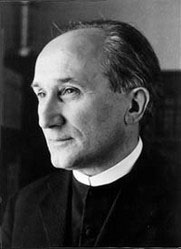

Who

was Romano Guardini (February

17, 1885 - October 1, 1968), and what were

some of his insights?

Born

in Verona, Italy, Guardini grew up in

Mainz, Germany. At an early age, he

matured into a "man of letters," a

Renaissance thinker, in pursuit of

life's meaning and truth. Working in

theology, philosophy, literary

criticism, and cultural analysis, he

held professorships in Berlin

(1923-1939), Tübingen (1945-1947), and

Munich (1948-1963). With his

approximately 70 books and 100 articles

and countless lectures, he touched the

hearts and minds of thousands of people,

including Hannah Arendt, Hans Urs von

Balthasar, Martin Buber, Dorothy Day,

Martin Heidegger, Thomas Merton, Olivier

Messiaen, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe,

Flannery O'Connor, and Karl Rahner, S.J.

Moreover, Pope Benedict XVI (formerly,

Josef Ratzinger) still frequently quotes

Guardini.

Born

in Verona, Italy, Guardini grew up in

Mainz, Germany. At an early age, he

matured into a "man of letters," a

Renaissance thinker, in pursuit of

life's meaning and truth. Working in

theology, philosophy, literary

criticism, and cultural analysis, he

held professorships in Berlin

(1923-1939), Tübingen (1945-1947), and

Munich (1948-1963). With his

approximately 70 books and 100 articles

and countless lectures, he touched the

hearts and minds of thousands of people,

including Hannah Arendt, Hans Urs von

Balthasar, Martin Buber, Dorothy Day,

Martin Heidegger, Thomas Merton, Olivier

Messiaen, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe,

Flannery O'Connor, and Karl Rahner, S.J.

Moreover, Pope Benedict XVI (formerly,

Josef Ratzinger) still frequently quotes

Guardini.

Romano

Guardini belonged to the generation of

German-speaking religious thinkers who – born

from the mid-1870s to the early

1890s – came

of age during the First World War. These

contemporaries of Adolf Hitler generated

many of the ground-breaking ideas and

approaches that still shape theology and

philosophy. Among Protestants were Karl

Barth, Rudolf Bultmann, Rudolf Otto,

Albert Schweitzer, and Paul Tillich. The

Jewish thinkers included Martin Buber,

Jules Isaac, Abraham Heschel, and Edith

Stein (who became a Catholic in 1922 and

died at Auschwitz in 1942). Among the

Catholics were Karl Adam, Odo Casel,

O.S.B., Romano Guardini, Josef Jungmann,

S.J., and Erich Przywara, S.J.

On God's presence

in human life

While

accepting the secularization of Western

society, Guardini sought to show that

the sacred is present and active in the

secular. Guardini directly challenged

secularism and atheism by promoting

worship, prayer, and

contemplation.

Furthermore,

he explained that a church should

delineate a sacred space. That is, it

should disrupt our preoccupations, and

open us to the wholly Other, the living

God.

According

to Guardini, the human conscience is

itself a sacred space in which God meets

a person. Developing this theme in 1928,

Guardini argued:

"God

speaks to us both from within ourselves

through the voice of our conscience and

also from outside ourselves in the

seeming coincidence of people and

events. The divine word from within us

clarifies the divine word from outside

us, and vice versa. A person's ethical

life arises out of the continually new

challenges coming from the interplay of

the inner word and the outer world . . .

The interplay of the word within us and

the word outside us simultaneously

engages the deepest elements of our

human existence and the riches of divine

revelation."

On the Lordship

of Jesus Christ

Guardini

saw that human beings orient their

personal freedom in one of three ways.

We can subordinate ourselves to a human

authority such as a parent, a spouse, a

boss, a pastor, a political figure, or

an organization. In its extreme, this

handling of freedom can bring about the

idolatry that "the Führer" demanded in

Nazi Germany. Secondly, we can assert

ourselves against all authorities. In

its extreme, this is the radical

self-assertion of the rebellious

teenager. Or, finally, we can entrust

ourselves to Jesus Christ who does not

enslave His followers but liberates them

to live for truth and life.

Guardini

acknowledged that Jesus Christ is the

transcendent, living person who can

encounter us in ways not unlike the way

that the Lord spoke to Saul (St. Paul)

on the road to Damascus. Christian

belief's "essence," Guardini taught, is

not a set of teachings but the risen

Lord. Indeed, the living Christ is

truth, reality itself who meets us as we

pursue the meaning and truth of our

lives. Using the phrases "the living

Christ" and "truth" interchangeably,

Guardini sought to bring truth to light.

Writing

his memoirs in the mid-1940s, Guardini

recalled his days in the Third Reich. In

particular, he observed that "truth" had

quietly stood with people during the

Nazi terror. For example, in January

1939, Guardini was summoned before the

Reich's Minister of Education, and told

that he could no longer lecture at

Berlin's Humboldt University. Hitler's

agent declared that the Reich was

stripping Guardini of his professorship

because he taught the Christian

"worldview" when he should be teaching

the Nazi "worldview." As Guardini

listened to the Nazi's hollow

statements, he sensed that Christ, Truth

itself, was silently supporting him in

this absurd situation.

Reflecting

on this moment and others similar to it,

Guardini wrote:

"Truth

is a power especially when we require of

it no immediate effect, but have

patience and figure on a long wait.

Still better, truth is a power when we

do not think in general about its

effects but seek to present it for its

own sake, for its holy, divine greatness

. . . Sometimes, especially in recent

years, I had the sense that truth was

standing as a reality in the room."

Accounting for

Christian hope

According

to 1 Peter 3:15, Christians must be

prepared to explain their faith to

anyone who requests "an accounting for

the hope that is in you." In doing this,

we can proceed in one of three ways. We

can simply repeat the words of the New

Testament and the church's creeds and

catechisms. This approach cherishes

truth, but it risks the eclipse of

meaning. Or, we can radically re-express

these teachings in a discourse that is

primarily reliant on today's

philosophical or psychological

categories. This method seeks relevance

but at the possible cost of faithfulness

to the Gospel. Or, we can fashion a

discourse that tries to integrate the

wisdom of the Bible and the Christian

tradition, on the one hand, and the

ideas and values of our society, on the

other. This theological approach is the

path that Guardini followed.

Throughout

his adult life, Guardini encouraged a

constructive, though critical, dialogue

between Christian faith and secular

culture. For example, in 1961, he wrote

that Christians must discern the

complexities, merits, and errors of

modernity, and address them on the basis

of divine revelation, as expressed in

the Bible and the church's life and

teachings. In this regard, he wrote:

"The

dangers of today's daunting

scientific-technological culture

challenge human beings in ways that are

now evoking fresh elements of the

Christian life, elements that were

previously dormant. How this challenge

will unfold and how Christians will

interact with the anonymous impulses of

the will to power, the drive for wealth,

and the effort to do everything is a

question that Christians have yet to

answer."

John's

Gospel inspired and guided Romano

Guardini's Christian belief and his

efforts to elucidate this belief. In

particular, the Johannine account of

Jesus' final prayer (John 17:15-19)

influenced Guardini, for although he did

not withdraw "out of the world," he did

not "belong to the world." Wanting "to

be sanctified in the truth," he

acknowledged that God's "word is truth."

As a disciple of Christ, Guardini

believed that the Lord had sent His

followers "into the world" to witness to

the truth. Hence, he unceasingly sought

"to be sanctified in the truth."

Copyright

© 1974-2010 Cardus

http://www.cardus.ca/