|

Love Stronger

Than Death: 21 Coptic Martyrs

.

a

brief report and interview with Coptic

martyrs' families

“ISIS thought the

killing of our relatives would destroy us.

It did not. It revived us.”

-

wife of 29-year-old martyr Samuel Abraham

February 15 (2019), marks

the fourth anniversary of the deaths of 20

Coptic Christian men from Egypt (Copts are the

native Christians of Egypt) and one Christian

man from Ghana — all martyred for their faith.

Last year, a church, The Church of the Libyan

Martyrs, was inaugurated and dedicated to the

lives of these men and their resolve to follow

Jesus.

In the days and weeks leading up to their

deaths, ISIS captors reportedly tortured the men

who had traveled the 1,200 miles to Libya to

find work and support their families. Militants

attempted to persuade them to deny Jesus in

return for their lives. They all refused. In

fact, during the barbaric execution, the men

repeated the words, “Lord Jesus Christ.”

“When I saw he

died with the name of Jesus on his lips,

I was very proud. I rejoiced!” – Malak,

father of martyred son

“We only knew

martyrdom from films, but martyrdom was

reintroduced and it strengthened our faith

because these people, these martyrs, lived

among us.”

For Malak, the reintroduction of modern-day

martyrdom on a worldwide scale is especially

sobering. He is the father of one of the 21

Coptic Christians killed by Islamic State

militants on the Libyan coast. Few will

forget the graphic images of the mass

beheadings in a video released and paraded

online around the world.

Excerpt from Open

Doors report, February 15, 2018 by

Lindy Lowry

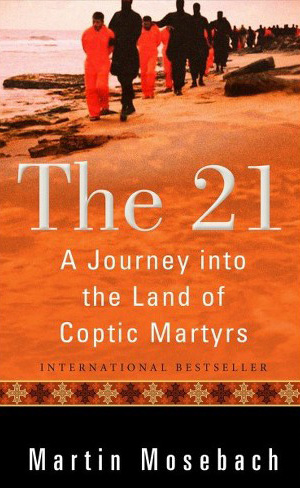

The 21: A Journey into the Land of Coptic

Martyrs

by Martin Mosebach

Martin Mosebach, an

acclaimed jornalist and novelist from

Frankfurt, Germany, traveled to Egypt and went

to the homes of the Coptic martyrs families.

He was started by the faith and serenity

Coptic Christians he met with. His interviews

and research culminated in the writing of a

book, The 21: A Journey into the Land of

Coptic Martyrs, published by Plough

2019. The following excerpt is from Chapter 9

of the book.

It had been dangerous to go to Libya seeking work.

The Arab Spring had plunged the country into

chaos, and public safety was effectively a thing

of the past. There had been violence against

Christians well before 2015, including several

murders. The priests of one Egyptian diocese – the

Holy Metropolis of Damanhur, in the Nile Delta,

who also looked after the Copts in Libya – ceased

their usual trips, as there was no reliable police

force left to protect them. But the families of

the Twenty-One needed the money, and going to

Libya was a shorter journey and posed fewer

bureaucratic difficulties than going to the Gulf

States. They were poor – just an inconspicuous

little group heading out to look for jobs

together. Who would care about such people?

And yet their departure was accompanied by a few

premonitions. Twenty-three-year-old Abanub, a

young man whose unusual features made it look as

if he might be from India, said to

a friend returning home to El-Aour from Libya in

2014 to get married: “You came back here for your

wedding this year, but in 2015 we will all

celebrate our wedding.” Might his listeners have

been reminded of the “marriage supper of the Lamb”

from the Book of Revelation, which all of them

would have been familiar with, in which the blood

of the sacrifice cleanses the robes of the

righteous until they are pure white? After the

fact, that is precisely how his enigmatic words

were interpreted.

Girgis (the elder) was also twenty-three and,

according to his father, always carried a

photograph of two Christians killed in a bombing,

saying: “I wish I were with them, and like them.”

Sameh phoned his family shortly before being

abducted – he had been in Libya for six months

already – and asked not only that everyone back

home pray for him, but above all that they look

after his little daughter.

Issam’s widow showed me a photograph people

considered prophetic. During a visit to the

Monastery of Saint Samuel, Issam had asked a monk

what the future might hold. Issam knelt silently

before him, and the monk put his hands around the

young man’s neck – that was the exact moment the

snapshot recorded. On the night the Twenty-One

were abducted, the monk had a dream: he saw Issam

and other men tormented by a large hound dog in

uniform, and then a dagger suddenly pierced his

chest.

Luka’s widow said that once, after hearing a

sermon on martyrdom, her husband had said: “I’m

ready.” He mentioned having an intuition that

martyrdom awaited him. He had often taken walks on

the very beach where he was later beheaded. He

also had a macabre sense of humor: she showed me a

photograph of him lying in a coffin he himself had

built. As I left, she gave me

a T-shirt with a print of her husband and Issam,

both wearing sparkling crowns.

Malak’s father, a fat, merry farmer in a gray

jellabiya, described a phenomenon that occurred

the night after the murder: a bright white light

appeared in the dark sky, “like a laser cannon.”

He and the neighbors spotted it even before news

of their sons’ deaths had reached them. He

recalled that, throughout the forty-three days

their sons had been held captive, the government

had kept all the men’s families in the dark,

without any news. “We didn’t know how they were

doing, but as soon as we saw the light, it was

clear: either they’ve been freed, or they’re

dead.” He had begun to join our visits to other

families, and let others confirm this miracle as

well; and indeed, they, too, had seen it.

Phenomena involving bright lights are a recurring

theme in Coptic narratives, and accompany almost

all major events the church has experienced over

the centuries.

The miracles didn’t stop, even after the massacre.

The little son of Samuel (the elder) fell to the

street from the third floor, and his arm was

broken in several places. When he regained

consciousness, he claimed his father had caught

him, and a few days later his x-rays showed not a

single fracture. Samuel’s sister, who entered the

door barefoot in a stained jellabiya, confessed

that for three days following the death of her

brother she had fought with God: “I blamed God!”

But then a bright light had appeared in the

heavens, Samuel’s face shining brightly from

within. “After that, twenty-one crowns appeared

around the light. From then on, I didn’t complain

anymore.”

Sameh’s son, who fell ill and began vomiting after

his father’s death, also saw him again: Sameh had

laid his hand on the child’s head and said, “It’s

going to be all right,” and the boy had

immediately felt well again.

Ezzat’s mother, a stout woman who had borne seven

other children and had a noticeably spirited

eloquence compared to most of the people I met

here, suffered a severe stroke a while after her

son’s death. Ezzat and Saint George had come to

her in a dream; her son had laid his hands upon

her, and she had been healed.

A childless Muslim woman came to Issam’s mother

for help – local Muslims often ask their Coptic

neighbors to pray for them: “Your God listens to

prayers and works wonders.” She gave the woman one

of Issam’s shirts. Maybe the woman wore it when

she lay with her husband – who knows? In any case,

after fifteen infertile years, she became pregnant

twice while in possession of the shirt.

The martyrs had often saved children falling out

of windows: after his death, Luka, too, had caught

his two-year-old nephew, saving him after he fell

from the fifth floor. This served as

confirmation – not just for the families, but also

for their neighbors and many others in the

surrounding countryside – that the martyrs were

indeed now with Christ. Their steadfastness had

led to their sanctification (this is why they were

portrayed wearing crowns) and they now served as

mediators of divine grace for their fellow human

beings on earth.

All of which is why their families didn’t care to

remember the grief, pain, and fear they felt

during the men’s captivity, nor the tears

unleashed by the news of their deaths. In fact,

they all went out of their way to avoid leaving me

with the impression that the decapitation of their

sons, brothers, and husbands had caused them any

misfortune. Naturally, they were depressed while

awaiting news, as they had been kept in the dark

and could only prepare for the worst. But when

they saw the video and knew with certainty what

had happened, their confidence had returned: “We

now have a holy martyr in heaven and must rejoice.

Nothing can harm us anymore.”

This also explains why the families handled the

execution video with such apparent ease. There was

an iPad in every household where the full-length,

uncut, unedited version could be watched.

Malak’s mother was the only one who refused to

look at the screen, while all the young men,

cousins, and brothers in the household, as they

had often done, stared at it, apparently

undisturbed, pointing out the men they recognized.

There could have been no better place to watch the

video – surrounded by the men’s families and

runny-nosed children, in rooms adorned with images

of the crowned Twenty-One, while a goat poked its

devilish-looking head through the doorway and a

calf next door wauled for its mother.

What would the murderers say about their video

being shown like this? Would it surprise them to

see how unflappable these simple-minded, poor folk

were; that these people had managed to

turn an attempt at triggering boundless terror

into something entirely different? Would they be

able to see that their cruelty had failed to

achieve its intended goal, that their attempt to

intimidate and disturb hadn’t succeeded?

Gaber’s hunched-over, barefoot mother – whose

house had resounded with unidentifiable voices

singing a hallelujah at the hour of his death, as

her Muslim neighbors also confirmed – was

quick to express her gratitude that her son had

become a martyr. Youssef’s family members – his

young widow with their little boy, his turban-clad

father, his mother holding an icon of her crowned

son to her chest – told me, as well as each other,

how happy they were when they realized that he was

in heaven. Gaber’s family had a similar response.

Hany’s mother also readily admitted her joy,

especially with regard to her four little

grandchildren: once they’re a bit older, they’ll

be so proud that their father is a martyr. Milad’s

parents also thanked God for their son’s

martyrdom,and the parents of Girgis (the elder)

recalled how their son had always wanted to become

a martyr. During his captivity they had not prayed

for his deliverance, but only that he remain

strong. He had remained strong indeed, and was now

the family’s pride and joy.

All these words were spoken not with fanaticism or

zeal, but rather with serenity and calm.

These were no Spartan mothers celebrating some

rigid ideal, but believers whose faith had been

forged and strengthened by adversity. Whereas

Georg Büchner’s Danton’s Death features Thomas

Payne asserting that pain is the touchstone of

atheism, in this case it turns out to be quite the

opposite: pain is the touchstone of faith and the

revelation of Christ.

Excerpt

from The 21, Chapter 9, by

Martin Mosebach, © Copyright 2019,

Plough Publishing House,

Robertsbridge, East Sussex, UK,

Walden, New York, USA, and Elsmore,

NSW, Australia.

Available from

Plough Publishing House and Amazon Available from

Plough Publishing House and Amazon

Behind

a gruesome ISIS beheading video lies the

untold story of the men in orange and the

faith community that formed these unlikely

modern-day saints and heroes.

Acclaimed

literary writer Martin Mosebach traveled

to the Egyptian village of El-Aour to meet

the families of the Coptic martyrs and

better understand the faith and culture

that shaped such conviction.

In

twenty-one symbolic chapters, each

preceded by a picture, Mosebach offers a

travelogue of his encounter with a foreign

culture and a church that has preserved

the faith and liturgy of early

Christianity – the “Church of the

Martyrs.” As a religious minority in

Muslim Egypt, the Copts find themselves

caught in a clash of civilizations. This

book, then, is also an account of the

spiritual life of an Arab country

stretched between extremism and pluralism,

between a rich biblical past and the

shopping centers of New Cairo.

|