Humiliation in the Incarnation

Jesus’ suffering began in his incarnation – when the eternal Son of God took on flesh (John 1:14). He was humiliated in becoming the God-man. In what was probably a hymn sung by the first-century church, Paul admonishes the earliest Christians to pursue humility by following the example of Christ:

Who, being in very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage; rather, he made himself nothing by taking the very nature of a servant, being made in human likeness. And being found in appearance as a man, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to death – even death on a cross!

Philippians 2:6–8

Though the cross was the pinnacle of Christ’s suffering, in the incarnation Jesus denied his divine privileges, “made himself of no reputation” (Philippians 2:7, KJV), became as a servant, and lived with the limitations and pain of being human. Jesus’ life on earth began in a posture of suffering and serving.

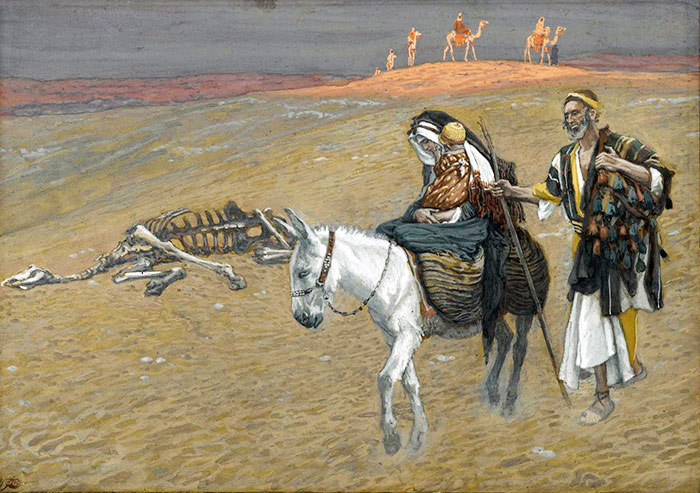

A Refugee

Following the visit of the gentile kings from the East who came to worship the Messiah (Matthew 2:1–12), the Jewish King Herod, fearful of losing his throne, began a systematic program of eliminating his future political opponents by putting to death all male children under the age of two (Matthew 2:16–18). Before the killing began, Matthew records:

An angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream. “Get up,” he said, “take the child and his mother and escape to Egypt. Stay there until I tell you, for Herod is going to search for the child to kill him.” So he got up, took the child and his mother during the night and left for Egypt, where he stayed until the death of Herod.

Matthew 2:13–15

Because of their forced displacement due to political tyranny and genocide, Joseph’s family fits the modern definition of a refugee. Jesus of Nazareth was a refugee. In the Lord’s displacement, he identified with sojourners, strangers, and the wandering Israelites in the Old Testament as well as the suffering diaspora church in the New Testament. He also identifies with people on the move who have sought refuge through the centuries, including those in the present day.

A Poor, Working Family

Following Jesus’ birth, Mary and Joseph presented him at the temple and offered “a sacrifice in keeping with what is said in the Law of the Lord: ‘a pair of doves or two young pigeons’” (Luke 2:24). According to the Law (Leviticus 12:8), a family ought to offer a sheep, but if they lacked the financial means, then doves or pigeons were also acceptable. The offering for Jesus was a poor family’s sacrifice.

Though Jesus apprenticed as a rabbi and certainly gained skills in reading and interpreting Scripture, he also apprenticed with his earthly father Joseph in the building industry. He worked with his hands and arrived home many days dirty and with body-aches, scrapes, and splinters. After Joseph’s death, Jesus’ family was put in a more vulnerable economic state, but the Lord continued to provide for his widowed mother and family through his work …

Suffering in His Call to Ministry

Each of the Synoptic Gospel writers capture the striking event of Jesus’ baptism (Matthew 3:13–16; Mark 1:9–11; Luke 3:21–22). While identifying with humanity in his baptism by John the Baptist, Jesus also invites the presence and power of the Godhead to the baptismal waters. The Spirit descends in the form of a dove as the Father verbally communicates his pleasure with the Son. In what seems like an instant, the jubilant celebration turns to hardship.

Using his customary economy of words, Mark bluntly writes: “Immediately, the Spirit drove him into the wilderness” (Mark 1:12, CSB). The same Holy Spirit who descended at Jesus’ baptism (and who shared fellowship with the eternal Son since eternity past) forced Jesus into the wilderness for forty days of testing. This period paralleled Israel’s forty years (Deuteronomy 9:18) and Elijah’s forty days in the wilderness (1 Kings 19:8). Weak from fasting, Jesus is approached by Satan on three different occasions. Satan tempts the Lord to turn stones into bread (to satisfy his physical hunger); to throw himself off the top of the temple (doubting God’s ability to care for him); and to bow do Satan in exchange for earthly kingdoms (power). To each temptation, the Lord responds with memorized…

Summary

Suffering frames the incarnation, life, and redemptive work of Christ. The Gospel of Jesus Christ is good news because of Christ’s suffering. To construct a Christian faith without the work of Christ – especially his crucifixion, burial, and resurrection – is to deny historic Christian teaching.

To follow Christ also means to embrace hardship, suffering, and even persecution. Before the cross and during Christ’s earthly ministry, Jesus called his disciples to suffer:

“Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me. For whoever wants to save their life will lose it, but whoever loses their life for me will find it.”

Matthew 16:24–25; also Luke 14:27.

As believers participate in God’s kingdom mission – between the now and the not yet of the kingdom – suffering becomes normal. In a sermon on suffering and God’s redemptive plan, Bishop Gregory the Great (540–604) stated:

The Father sent his Son, appointing him to become a human person for the redemption of the human race. He willed him to come into the world to suffer – and yet he loved his Son whom he sent to suffer. The Lord is sending his chosen apostles into the world, not to the world’s joys but to suffer as he himself was sent. Therefore, as the Son is loved by the Father and yet is sent to suffer, so also the disciples are loved by the Lord, who nevertheless sends them into the world to suffer.

Believers through the ages have identified with Jesus by embracing hardship. Christians are motivated to suffer and even welcome martyrdom because of their love for Christ because they worship a Suffering Servant.

This article is excerpted from Christian Martyrdom: A Brief History with Reflections for Today, © 2020 by Edward L. Smither, published by Cascades Books, Eugene, Oregon, USA.

Top image credit: The Flight Into Egypt, watercolor illustration by James Tissot, image source at Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York, USA. In the public domain.

Edward L. Smither is Professor of Intercultural Studies and History of Global Christianity and Dean of the School of Missions and Intercultural Ministry at Columbia International University, in Columbia, South Carolina, USA. He is an ordained deacon in the Anglican Church in North America. Before entering the world of higher education, he served for 14 years in intercultural ministry in North Africa, France, and the USA. He and his wife Shawn have three children.