In Christ, God has made a covenant with us – a covenant which we have joyfully received and entered into by faith and baptism. He has become our God and we have become his people … He has joined us together in a bond of steadfast love and faithfulness and has given us a particular call and mission … We desire to consecrate our lives to him, not simply as individuals, but as members of a people ….

The Community Covenant of The Word of God, 1970

In the winter of 1971-72 I attended a retreat in Monroe, Michigan. Called a “community weekend,” the retreat introduced its attendees to the concept of covenant community. My most vivid memory from that weekend is of Steve Clark standing before a chalkboard outline of Exodus 19-24, teaching about the covenant which God established with the people of Israel. From that teaching I recall his explanation of two Hebrew words, chesed (steadfast love) and emet (faithfulness). Those words characterize God’s irrevocable commitment to his people, but also serve as a summons to that people to reciprocate with chesed and emet towards their divine sovereign, and towards one another.

This teaching initiated a process of reordering my sense of self. To that point I had thought about my life in individualistic terms, even when responding to Jesus’s call to discipleship. But Steve had placed before me an explosive new idea that challenged my entrenched individualism: the notion of peoplehood. And he had done so through an exposition of the Hebrew Bible, with its narrative about God’s covenant with the people of Israel. Steve’s teaching impacted me, a Jewish follower of Jesus, with particular force. My identity as a member of the Jewish people and the body of Christ would never be the same.

… Steve befriended me in the months after that community weekend. Catholicism was a strange and alienating phenomenon to me in those days, and I would have been repelled if Steve had been like other religious Catholics I had known. But, in truth, he was not like anyone I had known. He had consecrated himself to Christ and his service, yet he had not pursued seminary education or priestly ordination. While not anti-clerical, he was emphatically non-clerical, a Catholic layman through and through. And, in addition to being smarter, more knowledgeable, and wiser than anyone I had ever encountered, he was entirely original in his way of thinking. The fact that he had a Jewish father and came from New York City was mere frosting on the cake. I was hooked.

Steve’s passion was to live fully for God, and his vocation was to evangelize, form disciples, and build community. His goal was to win wholehearted followers of Jesus, and to bring them together in a way that reflected the Church’s character as the people of God. Ecumenism did not come first in this vision, but it was a necessary consequence. Moreover, the shape of Steve’s ecumenical vision was determined by his grasp of the truth of Christian peoplehood. And this truth was rooted in the message of the Old Testament, and its witness to the identity of the people of Israel.

Peoplehood and Christian (Dis-)Unity

Steve’s 1982 Allies for Faith and Renewal paper on ecumenism manifests the logic of peoplehood without employing the term itself. In the course of his argument he contrasts dialogue ecumenism with cooperative ecumenism. The former focuses on bridging theological differences. This could suggest that the primary basis of unity is theological agreement, and the primary obstacle to that unity is theological disagreement. On the other hand, cooperative ecumenism – as expounded by Steve – focuses not on common theological affirmations but instead on committed relationships.

The center-point of Steve’s ecumenism is also the center-point of his life: a radical commitment to the person of Jesus.

“The cause of schism is putting something human above Christ as the point of unity and division in our personal relations, so that we join with and separate from others over something other than faithfulness to Christ. I believe there is a solution to this aspect of the problem of Christian unity, and the solution is our common commitment to Christ. It lies in together putting our commitment to Christ and to the cause of Christ in the world over everything else.”

quote from “Orthodox, Protestants, Roman Catholics: What Basis for Cooperation?, by Stephen B. Clark, Tabor House Publishing 1966

In other words, the solution is chesed and emet in relation to the one whom God has sent to renew Israel’s covenant and to redeem the world.

Our relationship to Jesus brings us into relationship with all those who follow him. We become brothers and sisters to one another, an extended family. And, “’lf we are brothers and sisters in Christ, we ought to be able to love one another. That does not just mean that we should feel sentiments of solidarity … It means that we should be committed to one another in an ongoing, practical way.” The language of committed love reflects Steve’s understanding of chesed and emet as the essential characteristics of God’s covenant with the people of Israel. The language of familial relationship points in the same direction. A people is not an institution, nor a party espousing a common ideology, nor a task force assembled to accomplish a particular objective. A people is an extended family whose identity spans past and future, and whose bonds can be damaged but not permanently severed.

One can discern the ecumenical logic of peoplehood in the article’s key biblical text. Steve cites Second Chronicles 28:1-15, which describes a war between the northern kingdom of Israel and the southern kingdom of Judah. The passage faults the victorious northern kingdom for failing to treat its defeated foe in a manner appropriate to their relationship as brothers. While the conflict itself was problematic, the eruption of military hostilities did not free the warring parties from an obligation to treat captives as family. Even while at war, the two kingdoms were expected by God to fight as those who were bound by familial ties. This biblical example displays the underlying context for Steve’s reflections on ecumenism: it is the Israel-like character of the Church as a New Covenant embodiment of the people of God.

The ecumenical logic of peoplehood likewise appears in Steve’s references to the work of Christopher Dawson, a Catholic historian from the mid-twentieth century. Dawson viewed Christian disunity as rooted in schism, i.e., relational rupture, rather than in heresy, i.e., irresolvable theological disagreement.

Steve’s lengthy quotations from Dawson include the following: “it is in the question of schism rather than that of heresy that the key to the problem of disunity of Christendom is to be found. For heresy as a rule is not the cause of schism but an excuse for it, or rather a rationalization of it. Behind every heresy lies some kind of social conflict, and it is only by the resolution of this conflict that unity can be restored.” Just as Christian unity must be viewed against the backdrop of the relational obligations of peoplehood, so the historical reality of Christian disunity must be seen pre-eminently as a violation of those obligations.

…

A Covenant Founded on God’s Chesed and Emet

An ecumenical vision of the people of God-that is, in essence, what Steve began to impart to that nineteen-year-old Jewish disciple of Jesus in the winter of 1971-72. The vision matured over the coming decades, at first through Steve’s continued teaching and example; later through immersion in the Messianic Jewish movement; and finally, through Messianic Jewish I Roman Catholic dialogue (in partnership with Fr. Peter}, and the formation of an international ecumenical fellowship of Jewish disciples of Jesus. At every stage of my journey, I have never lost sight of Steve’s chalkboard outline of Israel’s call to a corporate life of chesed and emet.

Looking back over the past half-century, Steve and I both have much to be grateful for. I rejoice with him in the rich life of the Servants of the Word and the Sword of the Spirit, and I am confident that he rejoices with me in the fruit that has been borne through my labor in the Messianic Jewish world. At the same time, all has not gone as we had hoped. Like biblical lsrael and the Jewish people through history, like the Christian Church in all its branches, like every movement of spiritual renewal in the whole people of God, our lives and our communities have experienced the fraying of covenantal chesed and emet. There has been shame as well as glory.

But it is a good thing to be humbled and chastened by a loving Father. On the other end of that half-century, we see clearly the heart of the covenantaI life of the people of God, which is not our chesed and emet but that of the One who has lifted us on eagles’ wings and brought us to himself. Despite our failures, and even by means of them, God has reaped a rich harvest. And we ourselves have learned to be faithful to our brothers and sisters, even when they stumble.

In all their frailty, Israel and the Church together bear witness to the eternal chesed and emet of the God and Father of our Lord Jesus the Messiah. His Spirit dwells ever among us, and inspires us to pray and work for the conversion of souls, the illumination of Israel, the unity of the Church, and the second coming of the Messiah. God is faithful, and he will do it.

This article by Mark Kinzer is excerpted from, “Our Hope of Sharing the Glory of God” Essays in Honor of Stephen B. Clark. Copyright © 2023 The Servants of the Word. All Rights Reserved.

- See related article, Orthodox, Protestants, Roman Catholics: What Basis for Cooperation?, by Steve Clark

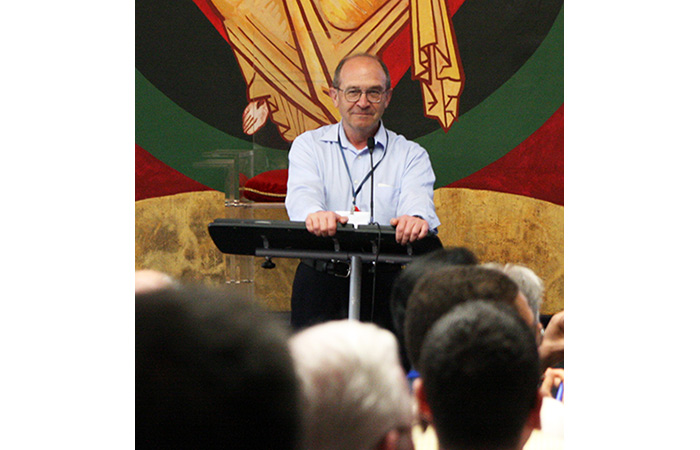

Top image credit: Steve Clark addressing an international meeting of the Sword of the Spirit community coordinators in Santo Domingo 2008, image © The Sword of the Spirit.

Dr. Mark Kinzer is Senior Scholar and President Emeritus of Messianic Jewish Theological Institute, a graduate school preparing leaders for service in the Messianic Jewish movement. Dr. Kinzer lives with his wife, Roslyn, in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where he also serves as Rabbi Emeritus of Congregation Zera Avraham, a Messianic Jewish synagogue which he founded in 1993.

He has been involved in ecumenical work since the 1970s, and has been a member of the Messianic Jewish – Roman Catholic Dialogue Group since its inception in 2000. He had an active teaching and leadership role for some 20 years (1970’s – 80’s) with The Word of God and the Servants of the Word in Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA and also with the wider network of international communities, called Sword of the Spirit. At its peak growth of 1400 people in the 1980s, The Word of God community comprised a diverse membership of Christians from many different traditions and denominations, including Catholics, Protestants, Orthodox, Pentecostals, and Messianic Jews.

Dr. Kinzer has written a number of articles and books, including Living With a Clear Conscience: A Christian Strategy for Overcoming Guilt and Self-Condemnation (1982), and Searching Her Own Mystery: Nostra Aetate, the Jewish People, and the Identity of the Church (2015), with a forward by Christoph Cardinal Schonborn, and Jerusalem Crucified, Jerusalem Risen: The Resurrected Messiah, the Jewish People, and the Land of Promise (2018).

Hi dr Kinzer I am Carlos Salinas I live in Mission Tx I am very impressed by your curriculum I serve as a Senior coordinator in Family of God Community life as a part of the Sword of the spirit, I went to Jerusalem and felt attracted by the way that Christ lived, any way I would like to be in contact with you, also at this moment I am the coordinator of the Charismatic renewal in the Diocese of Brownsville (where I live)

God Bless you and by the way we follow every Saturday the Shabbat (according to the notes you provided in the past)

Thanks