Introduction:

The Bible is a treasure chest of words and stories that are bristling and living. Each of them teems with energy, sparking out with flashes and flames. But our wont is to treat it like a locked cupboard that only certain custodians have the key for.

Rather, let us agree that the Bible itself teaches that it is meant to be unleashed. It is ready to leap into action and overturn lives and perspectives on life. Every time we read it, we should let “serendipity” have its reign, ordering our time and thoughts. In many ways, the Bible should be unpredictable in its meaning and consequences, not trapped in traditions and archaeology. Let us unharness its potential. Let tradition and archaeology come to our aid in the process.

It is our encounter with its divine compiler and organizer who uses what seem like hidebound and mind-numbing chronicles, memorized and passed down, to incarnate within us again and again. But such miraculous and seemingly magical things depend on an imagination that awakened by the serendipitous Holy Spirit, constantly brooding over us in our prayerful reading. We are but participants in how the Holy Spirit activates it, actors and reactors in its serendipitous invasion into time and space.

Let us approach Bible reading with expectation and imagination. Let us find the pauses and lacunae in our priorities when the inner spirit of a person is vacant, yet fully awake. We must be like those who watch for dawn to break, breathless and alert, studying every flicker of light and wisp of sound for an approaching intruder or cheerful dawn. When either occurs, our whole purpose for reading the Bible is fulfilled. We discover who we are and what is our place as we listen and read the Bible.

I wait for the LORD, my soul waits, and in his word I hope. My soul waits for the LORD more than watchmen for the morning, more than watchmen wait for morning. Awake, O my soul. Awake, my glory, I will awake the dawn.

How I got involved in Performative Bible Study

Eight years ago, a colleague invited me to explore a new way of teaching the humanities. So I attended a conference at Barnard College and quickly discovered that this new pedagogy (called Reacting) put the burden of learning more on the student than on the teacher. I had a full gamut of courses that I would teach every semesters, from ancient history to comparative religion to modern European history; and I was getting worn out by the daily lecturing routine. This new approach turned over the reins of the classroom to the ones who are learning. They have far more energy than I, and with a little guidance can channel it into learning enthusiasm.

The main way this pedagogy works is through engagement. If you put the student or participant in the role of someone or something in the story, you can now make that person “perform” or “react.” This in itself forces responsibility on the learner instead of on the teacher. When you factor in team members and “opposing” teams, you only compound the urgency of the learner to improve the performance by study and preparation.

The one in charge needs to choose what the lesson of any given session is. Then the ground rules need to be laid out for all the participants. A teacher or group leader needs to be knowledgeable enough to navigate the way ahead for the learners. The one in charge crafts the questions to be raised and helps the various teams or performers get ready. Then, when the performance session begins, he or she needs to monitor and occasionally intervene to make sure that the interchange among participants stays on track. At the end, the teacher or group leader calls everyone together and “debriefs” to make sure that everyone gets a chance to give their impressions of the exercise, even while summing up the main points learned.

Memoirs of an Unfinished Tale:

A Performance of Acts of the Apostles

By Mark F. Whitters

Published by Cascades Books, Eugene, Oregon , 2017

175 pages

An excerpt from the Preface:

What if Luke had to reteach the basic lessons of his history of the early Church? What stories contained the nuggets he would impart to the neophyte recipient he called Theophilus? How would he communicate his point while livening up the details for someone who either was not present for the actual event or had not paid sufficient attention the first time he wrote Acts of the Apostles?

This is Luke’s retelling his second book to a younger and still eager Theophilus. According to the sequence, the two books are bridged by the life of Jesus – and this current work focuses on what happens after Jesus. It presumes Theophilus knows the details of the Gospel of Luke. Luke realizes that if he is to arouse his reader to act on what he remembers about Jesus, he must again re-enact his stories and replay the events before Theophilus’s very eyes. He knows that Theophilus is interested in history not as a dry memorization of facts nor of a metal chain of events, but as a compendium of lessons that guide growth and change. History, thinks Luke, unfolds as episodes, cohering around an intelligible theme with drama and suspense. So, not unlike a play, it requires imaginative performance to both entertain and provoke an audience to react.

This is a fresh way of presenting the Bible, a method based on a rapidly growing movement in college and university classrooms called “reacting.” It is in line with more traditional ways of understanding Scripture as performed in the context of liturgy. At the same time this book challenges individuals with creative poems and illustrations and a built-n system of application questions for daily reading.

How to Prepare a Performative Bible Study

Performative Bible study allows participants to go back into the biblical world and explore for themselves how they would have responded to questions that a passage poses. It is based on a new university pedagogy called “reacting,” where instructors fashion learning games and exercises to draw students into learning about the humanities.

Below is a video that gives a demonstration of performative Bible study, based on how a group of twelve college-aged students “played” Luke 24. If you would like to bring performative Bible studies to your church or organization, Memoirs of an Unfinished Tale offers an imaginative script, based on the Book of Acts. Purchase the book here.

How one smaller group used this approach for the Gospel of Luke:

A larger group doing performative Bible study with the author:

Step by Step: A Guide for Leaders (video at Vimeo)

Some quick advice about running a performative Bible discussion from Memoirs of an Unfinished Tale–and you do it in an hour:

- Ahead of time: the leader and “the script” (variable prep time)

- Choose a passage that is short and dynamic with action and potential team dynamics.

- Dissect the passage based on guide or skill: What is the overall context? What is going on? What is the Scripture’s message?

- Design a performance that allows interaction between teams/positions and think of the questions that the performers should be aware of that reflects their position.

- Compose a role-playing guide for each of the teams/positions.

- The discussion begins: the leader as “director” (10 minutes)

- Describe the scene/context of “the script” for everyone.

- Assign the teams.

- Distribute the role-playing guide to each team/position.

- Introduce the concept of performance and its basic ground rules.

- Team meetings: team “rehearsal” (10-15 minutes)

- Read passage carefully in team meeting.

- Assign roles to team members as needed.

- Rehearse team position and think about their role.

- Consult with “director” as needed during meeting time.

- “Showtime!”: Interactive performance among teams/positions (20 minutes)

- Interview with each team and its members based on designed questions.

- Dialogue or cross-examination among other teams and their members.

- Conduct “business” that passage or script has designed.

- Guidance as needed by leader throughout.

- Debriefing and back to “reality” (10 minutes)

- How did each performer react to their position or role?

- What did each team and performer learn as the performance unfolded?

- Leader sums up what performance showed and what the passage seemed to teach.

Ideal discussion specifications:

- Four teams/positions

- 15-30 people in the whole group, thus, 3-7 people on each team

- As many actors per team as the “script” allows

- Duration: 50-60 minutes

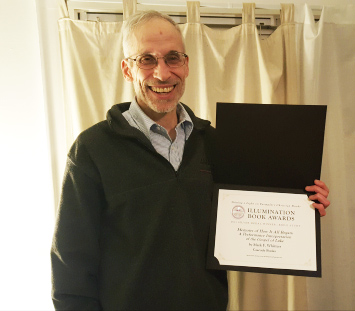

Recent Book Award:

The Illumination Book Awards, “shining a light on exemplary Christian books,” recently announced “Memoirs of How It All Began” as the 2020 Silver Medal winner in the Category “Bible Study.”

Mark Whitters is a life-long member of the Servants of the Word, an international ecumenical brotherhood of men living single for the Lord. Since August, 2001 (25 years and counting) he has been a founding member of Detroit Community Outreach. He networks with local pastors, teachers, and volunteers who are involved in racial reconciliation and community building in Detroit, Michigan, USA.

Mark F. Whitters is an author and university instructor. He has written two books: Memoirs of an Unfinished Tale: A Performance of Acts of the Apostles (2017), and Memoirs of How It All Began: A Performance Interpretation of the Gospel of Luke (2019), both published by Cascades Books, Eugene, Oregon, USA.

Mark completed two M.A. degrees in Classics at The University of Michigan (1991) and in Near Eastern Studies at the University of Minnesota (1994). His PhD in religious studies is from The Catholic University of America, where he focused on Syriac Christianity in the Middle East. He has been a full-time lecturer at Eastern Michigan University in the Department of History and Philosophy since 2007. In 2010-11 he was selected by EMU as the “lecturer of the year.” That same year, he learned about the “Reacting” pedagogy through a conference at Barnard College and began to use it often in his classes. In 2012 he took a senior lecturing post in the newly formed program in Jewish Studies.