The purpose of this history is to reveal the works of God in calling together Christians from many churches to form an ecumenical, charismatic community of covenant communities, the Sword of the Spirit. It is not an exhaustive history, nor can it discuss in depth the many struggles and challenges that needed to be overcome in the building of these communities.

The Sword of the Spirit is part of a larger movement of covenant communities throughout the world, some of them joined together in networks, some standing on their own. This movement of communities is a sign of the times, when Christians are beginning to bridge the differences that have long divided the Church of Jesus Christ and beginning to realize that what they have in common is much more important than what separates them. In the face of a society grown more and more hostile to historic Christianity, the support of newly found brothers and sisters in Christ is very welcome.

The immediate occasion for this history is the fiftieth anniversary of the first commitments made, in September 1970, to a covenant that binds together brothers and sisters in what has come to be known as covenant community. It follows close upon the fiftieth anniversary of the beginning of the charismatic renewal in the Catholic Church. The Sword of the Spirit, and the larger covenant community movement of which it is a part, has its origin in this charismatic movement.

The jubilee celebrations of the Catholic charismatic renewal, especially the gathering in Rome on Pentecost 2017, included a celebration of covenant community. It was a time for looking back at what God has done in the past and for considering what he is calling us to in the future. Therefore we begin the story of the Sword of the Spirit with a consideration of the origin of the Catholic charismatic renewal, and of the larger Pentecostal movement that preceded it.

Most of the founders of covenant community were also founders of the Catholic charismatic renewal, and most of the earliest participants in that renewal have been, for at least a period of time, participants in covenant communities – many still are. Whether organized in communities of the kind bound by covenant or not, the charismatic renewal has always had a powerful communitarian element, bringing people to a new understanding of one another as brothers and sisters in Christ. Moreover, just as the Sword of the Spirit and many other covenant communities are ecumenical in nature, the Catholic charismatic renewal owes its existence in part to the ecumenical openness encouraged by the Second Vatican Council. That Council’s ecumenical concern was itself a fruit of the ecumenical movement which arose early in the twentieth century.

20th century of the Holy Spirit and Pentecostal movement

Sister Elena Guerra (1835-1914), foundress of the Oblates of the Holy Spirit, a religious order of women, wrote several letters to Pope Leo XIII, in which she urged him to encourage the Catholic Church to greater devotion to the Holy Spirit and awareness of his work. Pope Leo wrote two encyclicals about the Holy Spirit during the 1890s, followed by a letter to all Catholic bishops in 1902, mandating regular prayer to the Holy Spirit, especially between the feasts of Ascension and Pentecost.

In her ninth letter to Pope Leo XIII, October 15, 1900, Elena begged the Pope to exhort all Catholics to pray for the new century and to place it under the sign of the Holy Spirit. “Most Holy Father, I humbly present with confidence to your Holiness that the new century may begin with the hymn Veni Creator Spiritus [Come, Creator Spirit] to be sung at the beginning of the Mass of the first day of the year.”[1]

On January 1, 1901, the first day of the first year in the twentieth century, he intoned the hymn Veni Creator Spiritus in the name of the whole Church. On the same day, an event took place in Topeka, Kansas, that marked the beginning of a great revival in the power and gifts of the Holy Spirit destined to sweep throughout this country and around the world.[2]

What happened next was the dramatic beginning of the Pentecostal movement. It began not only geographically, but also theologically, far from Rome, in a Protestant Bible college in Topeka, Kansas, USA. The movement’s roots in Protestantism went back over a century before that to the 1700s in some of the Methodist churches that had been founded by John Wesley. Wesley taught that Christians can undergo the experience of “entire sanctification,” which his colleague John Fletcher called the “Baptism in the Holy Spirit.” Although this became a teaching of the Methodist movement and was experienced by many believers, it was not typically connected with manifestations such as speaking in tongues. However, in Britain during the middle of the nineteenth century, the Catholic Apostolic Church, also known as the Irvingites, after Edward Irving, one of their founders, did experience some of these gifts.[3]

During the nineteenth century, many Protestant preachers and teachers in both Britain and the United States taught the doctrine of sanctification through an experience of a “second blessing” after conversion, sometimes referred to as a baptism in the Holy Spirit or a “baptism by fire.” This teaching, which came to be called “Pentecostal” is to be found in the preaching of leaders in the Baptist and Methodist traditions, including such well-known figures as C. H. Spurgeon and Dwight L. Moody.[4]

The Pentecostal movement, as it is called these days, began with a former Methodist preacher, Charles Fox Parham (1873-1928). Parham had experienced what he called a miraculous healing from a chronic condition that had prevented him from walking without crutches, after which he became an independent evangelist in the Methodist Holiness movement, preaching “the necessity of being baptized in the Holy Spirit as the only way to escape the coming end-time Great Tribulation.”[5] After attempting to found several missions, he settled in Topeka, Kansas, and founded the Bethel Bible School in 1898.

Parham and his students undertook a program of biblical study to determine a particular sign of the baptism in the Holy Spirit. In December 1900, they concluded that the evidence of baptism in the Holy Spirit was speaking in tongues. Parham called for an all-night prayer service on New Year’s Eve 1900, and it was during that service that he laid hands on and prayed for Agnes Ozman, one of his students, and she began to speak in what Parham said was identified as Mandarin Chinese. Other students came to speak in what Parham later claimed were over twenty different languages.[6]

As the Pentecostal movement spread in America, visiting pastors and American missionaries carried it to many countries throughout the world. Thomas Ball Barratt, the English Methodist pastor of a church in Oslo, Norway, came to the United States in 1906, visited Azusa Street, and was baptized in the Holy Spirit. He returned to Oslo in 1907 and began a revival that attracted pastors from many European countries, including Britain and Sweden, who went home and began Pentecostal revivals and churches. Visitors from other countries did the same, and both American and European missionaries spread the movement to Asia, Africa, and Latin America, founding churches that were soon led by native-born preachers.[7]

Neo-Pentecostal movement

American Episcopal bishops in 1962 accepted the renewal into the church provided that the participants continue to participate in the life of the church. This example was followed by other Anglican churches, and the neo-Pentecostal movement came to incorporate many clergy and bishops, as well as thousands of lay members, throughout the world. Similar movements took place in the Lutheran, Presbyterian, and other Protestant churches.[8]

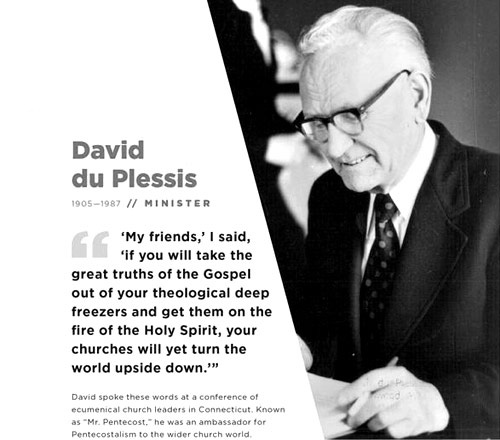

At the same time as the mainline denominations were coming to accept the Pentecostal experience, some Pentecostals were beginning to reach out to the other churches. The undoubted pioneer in this effort was the South African-born pastor David du Plessis. He was inspired by a prophecy delivered to him by the British Pentecostal evangelist Smith Wigglesworth that he should bring “the message of Pentecost to all churches.” When du Plessis relocated to the United States in 1948, he began to develop ecumenical ties, first with the National and World Councils of Churches, and then with the Catholic Church. He attended the Second Vatican Council as the accredited Pentecostal observer, although not officially representing any Pentecostal church. Indeed, his own church, the Assemblies of God, revoked his ministerial credentials in 1962 for this activity, although he was reinstated in 1980, seven years before his death.[9]

By 1967, this “neo-Pentecostal movement” had been accepted by the major Protestant denominations in the United States. The movement had been publicized in such major news magazines as Time and Newsweek, as well as in the leading Evangelical magazine, Christianity Today.[10] More significant for the spread of charismatic renewal, however, was the work of the American Episcopalian writers John and Elizabeth Sherrill. They collaborated with the Assemblies of God pastor David Wilkerson in writing The Cross and the Switchblade, which described Wilkerson’s work converting gang members in New York City, in 1962. In 1964 the Sherrills published a history of the neo-Pentecostal movement, including their own participation in it, They Speak with Other Tongues. These books were to prove central to the spread of Pentecostal or charismatic renewal.

Although there were examples of renewed local churches like Bennett’s St. Luke’s, or Graham Pulkingham’s Church of the Redeemer in Houston, Texas, neo-Pentecostalism generally took the form of small prayer groups meeting in churches or private homes. It was in the Catholic charismatic renewal that the movement towards covenant community arose. While sparked by contact with Protestant neo-Pentecostals, covenant community also had roots in streams of Catholic renewal, streams that envisioned not only individual spiritual revival but also the emergence of community.

Cursillo movement and Catholic charismatic renewal

The charismatic renewal in the Catholic Church began in 1967, but the ground had been prepared for it by a group of young Catholics who were looking for a revival of faith in the Church in the years during and immediately following the Second Vatican Council. The group began to coalesce at the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana, in late 1963. The group included Bert Ghezzi, a graduate student in history; George Martin, a graduate student in philosophy; and Steve Clark, another philosophy graduate student.

Clark emerged as the leader of the group. He had converted from atheism to Christianity and was baptized into the Catholic Church during his undergraduate days at Yale University, where he had noticed that “Catholics at Yale who associated with each other … usually grew in faith and holiness.”[11] Since he had a convert’s zeal to share his faith, he was distressed that many of his fellow Catholic students seemed indifferent: “they tended to feel that everyone was basically a Christian and that all that was needed was an improvement in society’s moral tone.”[12] He graduated from Yale in 1962 and spent the following year studying in Tübingen, Germany, on a Fulbright scholarship before entering graduate school at Notre Dame. He had spent the summers of 1961 and 1962 in Mexico doing mission work. Before he went on the first mission he learned about the Cursillo movement, and while in Mexico, he had the opportunity to meet participants in it.

Through his experiences at Yale and in Mexico, Clark had developed a vision of the church as a community. In 1963, while he was still in Germany, he had written,

Christ wants the man; and he wants the man in a personal relationship – love. That is why the center of any Christian endeavor must be the community of people who are united to Christ and each other. They have a common vision, and they have a common spirit, because the gift of Christ is the Holy Spirit who moves them to activity. The church is a community that works together, not simply a service station where individuals and families come together periodically to be fueled up with grace so they can go out and do their jobs. It is a personal relationship between Christ and his people, not an organizational structure.[13]

He saw in Cursillo a way both to encourage the personal relationship with Christ that would be necessary for this vision and to build the community that would result from the shared call to this relationship.

The Cursillo movement had begun in Spain in 1949, led by Bishop Juan Hervas and the layman Eduardo Bonin. They believed that the only way that the Church could survive was for men to live intense Christian lives. Therefore, they started what they called Cursillos de Cristiandad (Short Courses in Christianity), where the participants would be asked to commit themselves to live this intense and militant Christianity, followed by regular small and large group meetings to encourage one another’s faith and apostolic activity. The Cursillo spread from Spain to Latin America, and thence to the United States, with the first English-language Cursillo given in San Angelo, Texas, in 1961. Soon after Clark arrived at Notre Dame, he heard of a Cursillo being given in nearby East Chicago, Indiana, and attended it.

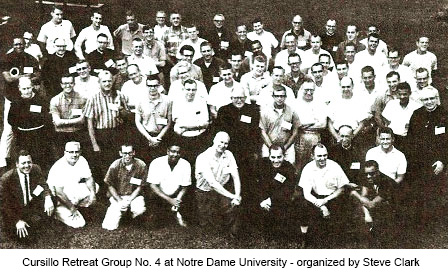

Soon Clark arranged for a Cursillo to be given at Notre Dame, which was attended by George Martin, Bert Ghezzi, and a number of other active Catholic graduate students and professors. Following the Cursillo, the participants continued to meet to encourage one another and to pray for renewal on campus. They also worked on strategies to transform campus life in a more distinctly Christian direction. In an early paper Clark, Martin, and others outlined a plan to bring about “a deeper dedication to Christianity” at the university.

There are two factors here…. The obvious one is that group action is the only feasible means to some ends. The more important one is that such action flows from the Christian community and can thus be more fruitful.

The explicit centrality of a conscious Christian community to the plan is a hallmark of this presentation. Although [water] Baptism ipso facto makes men members of the Christian community, they have not often been aware of the importance of this fact for their lives.[14]

While the authors make clear that they consider the church to be the Christian community in one sense, the conscious community of which they speak is a local community, without which it is impossible to participate fully in the larger church. They go on to outline various types of groups, with the qualifications for group leaders and other roles. They also discuss “study weekends” to “orient individuals to Christian community life.” This should lead to the response “to God’s call to complete self-dedication to him in Christ.” They also see Cursillo as part of the plan for those who are ready for it. Clark and George Martin led the development of the program for the study weekend, an adaptation of Cursillo for the student setting.

The second Cursillo at Notre Dame, held in early 1964, witnessed the conversion of Ralph Martin. An undergraduate studying philosophy with a special interest in Nietzsche, he had thrown off his Catholic upbringing and become an outspoken atheist. Circumstances had led him to share an apartment on campus with Phil O’Mara, a graduate student in American literature and one of the original Cursillo group. O’Mara persuaded Clark—with some difficulty since Clark was familiar with Martin’s attacks on Christianity—to allow Martin to make the second Cursillo. He went into the weekend an atheist and came out a fervent Christian. Ghezzi, who was present on the weekend, later said, “I never saw such a complete U-turn in my life.”[15] Martin went from preaching atheism to preaching Christ with even greater enthusiasm.

Several other students and faculty members also made Cursillos and joined the group. These included Kevin Ranaghan, a theology student, and his wife Dorothy; Fr. Charles Harris, one of the priests on the faculty; Dr. Paul DeCelles, a physics professor; and undergraduates Jim Cavnar and Gerry Rauch. All of these would later play a role in the emergence of charismatic renewal and the formation of covenant community. In was Fr. Harris and Cavnar who completed the program for that study weekend, now renamed the Antioch Weekend.

Charismatic prayer groups at Notre Dame, East Lansing, and Ann Arbor

Charismatic prayer groups began at Notre Dame and in East Lansing. After Easter, a group from Michigan State including Martin and Clark joined the group in at Notre Dame for a weekend retreat that has been called the “First International Conference” of the new movement. Through Notre Dame alumni, prayer groups began on other campuses.

The Notre Dame group enjoyed early support from several of the Holy Cross priests on the faculty, including Fr. Edward O’Connor and Fr. Charles Harris. The group in East Lansing, led by Steve Clark and Ralph Martin, initially met no opposition from the pastor of St. John’s Student Center where they worked, but during the summer, negative reports led him to fire Martin and Clark. By this time Gerry Rauch and Jim Cavnar had joined them. These two who had just graduated from Notre Dame and had been among the members of the Cursillo group who participated in the first charismatic prayer meetings. All four were evicted from their apartment and their meagre belongings thrown out on the street while they were attending a convention in Colorado.

George Martin, also working in the Lansing area at the time, rescued their possessions and the men were able to find temporary housing. While passing through Ann Arbor, Michigan, they offered their services to St. Mary’s Student Chapel on the campus of the University of Michigan and were accepted.[16] They moved into an apartment over a convenience store near campus. The East Lansing prayer group, which had been meeting at St. John’s Student Center, found a new place to meet and continued to grow.

Things were beginning to develop quickly. By October of that same year (1967), Steve Clark, Ralph Martin and others organized monthly Days of Renewal in Williamston, near East Lansing. Members of prayer groups from all over Michigan came to pray together and receive teaching. In the Grand Rapids area in western Michigan, Ghezzi was teaching at the recently opened Grand Valley State College where he started a charismatic prayer meeting. Prayer groups had also begun in the Detroit area. On 16 November 1967, the first prayer meeting took place in Ann Arbor at the apartment shared by the four men working at St. Mary’s, and was attended by some of the students they had met in the course of their work, some of whom had already been baptized in the Holy Spirit and had attended the Day of Renewal in Williamston. Although Gerry Rauch, who led that meeting along with Jim Cavnar, remembers it as rather dull, the participants asked to return for more, and the meetings became a regular Thursday evening event.[17] In one of the early prayer meetings, they heard a prophetic message telling them, “You will reap a harvest you did not sow…I will send many to you… A shining cross of my body, of those you work with, will be raised up among you.”[18] The fifteen or so participants who heard that word had no idea of the community that would grow from this little meeting.

This article © 2020 The Sword of the Spirit is adapted from A Brief History of the Sword of the Spirit, by Bruce Yocum, Bob Bell and Henry Dieterich, commissioned by the International Executive Council of the Sword of the Spirit to mark the 50th anniversary of covenant community.

[1] Oblates of the Holy Spirit, “Come Holy Spirit,” a pamphlet about Bl. Elena Guerra, no other data available about publication. [Note from Mansfield, p. 27]

[2] Mansfield, p. 27.

[3] Vinson Synan, Century of ihe Holy Spirit: 100 Years of Pentecostal and Charismatic Renewal, 1901-2001 (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 200) pp. 15-24.

[4] Ibid., pp. 25-35

[5] Robert Owens, “The Azusa Street Revival: The Pentecostal Movement Begins in America” in Synan, Century of the Holy Spirit, p. 43.

[6] Ibid., p. 44.

[7] See Gary B. McGee, “To the Regions Beyond: The Global Expansion of Pentecostalism” in Synan, Century of the Holy Spirit, pp. 69-95.

[8] See Synan, pp. 155-208 for a church-by-church overview of the progress of neo-Pentecostalism.

[9] Synan, 361-63.

[10] See Synan, p. 153, 154.

[11] Jim Manney “Before Duquesne: Sources of the Renewal” New Covenant, 2:8 (February 1973), pp. 14.

[12] Steve Clark, quoted ibid.

[13] Stephen Clark, “The Bureaucracy of Believers” New Generation: A National Journal of Student Opinion 1:1 (Summer 1963), p. 18.

[14] “A proposed starting point for an apostolic plan for Notre Dame.” Steve Clark papers.

[15] Quoted in Manney, “Before Duquesne,” p.13.

[16] Interview with Gerry Rauch, 22 April 2017.

[17] Ibid,

[18] Mary Ann Jahr, “An Ecumenical Christian Community: The Word of God, Ann Arbor, Michigan” New Covenant4:8 (February 1974), p. 5.

This is part of the series: A Brief History of the Sword of the Spirit

- Bruce Yocum, leader of the writing team, and author in his own right, was part of the communities movement since 1968 and held various leadership roles for more than 50 years. He was instrumental in the formation and growth of numerous communities in the Sword of the Spirit.

- Henry Dieterich has been present in Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA, for most of the time since the beginnings of the communities movement. He holds a doctorate degree in history from the University of Michigan and did most of the actual writing of the history, fostering a rigorous standard of historical research and accuracy. Henry lives in Ann Arbor with his wife Roz and is a member of Word of Life there, a community of the Sword of the Spirit.

- Bob Bell was also present in Ann Arbor for decades, starting in the autumn of 1967 and an eyewitness to much of the early history of the Sword of the Spirit and the communities movement. He was also part of the start-up team for Jerusalem, the Sword of the Spirit community in Belgium. He works for the Sword of the Spirit administrative and editorial staff and has made his home in London, England, and is also part of Antioch, a member community of the Sword of the Spirit.

I want to thank the organizers for this wonderfull article. I just have a question: They talk about Steve Clark, Bert Ghezzi and there is this third person called, sometimes, George Martin and other times Ralph Martin. Are they different people?